Biological inoculants have come a long way in helping growers raise stronger plants and reap more robust yields.

Today’s inoculants, like Vault® HP from BASF and many others, help maximize nitrogen fixation, enhance nitrogen availability, add vigor to plants, protect against stress, and contribute to greater yield potential.

The practice of mixing “naturally inoculated” soil with seeds was introduced in the 1890s, becoming a recommended method of legume inoculation in the United States. In 1896, Nitragin became the first patented product registered for plant inoculation with the beneficial bacterium rhizobium (a living microorganism in the soil).

So with such a deep history of use and a bright future as an increasingly innovative and important practice in agriculture, what actually is an inoculant?

Bacteria that are beneficial

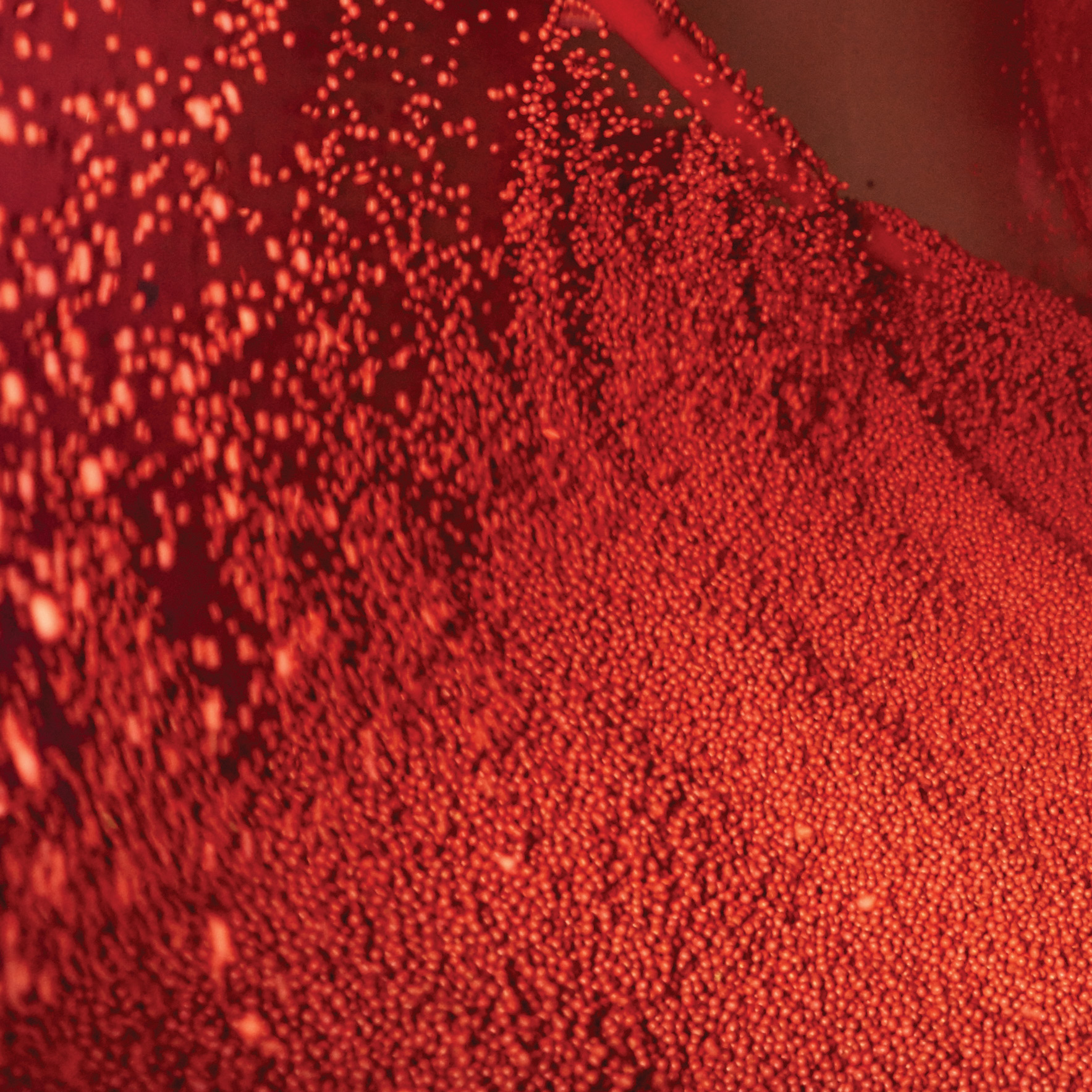

Biological inoculants are formulations of beneficial bacterial strains — rhizobia being just one — contained in an easy-to-use and economical carrier material (either organic or inorganic).

In essence, an inoculant is the means of transporting helpful bacteria from the microbial production facility to the living plant.

With growers across the globe looking for new and effective ways to maximize plant health and yields, inoculants offer an array of beneficial effects, including:

- Nitrogen fixation in legumes

- (A)symbiotic nitrogen fixation in non-legumes

- Biocontrol of soil-borne diseases and other conditions

- Solubilization of certain soil minerals

- Nutritional/hormonal effects and other (a)biotic mitigation activity

Today, seed and soil inoculants contribute to a wide spectrum of bioactivity, including:

- (A)symbiotic nitrogen fixation (e.g., rhizobia, Azospirillum, Gluconoacetobacter, Azotobacter)

- Phosphate solubilization

- Sulphur oxidation

- PGPR/ISR activity (plant health), including gene priming

- (A)biotic stress alleviation (e.g., drought/water, salt and heat)

- Biopesticidal/biorational activity

So how do rhizobia fit into the equation?

Rhizobia are living microorganisms (soil bacteria) that “fix” nitrogen (N) — that is, they take N from the atmosphere and hold it for a time in the plant — when in a unique symbiotic relationship with the host legumes. They’re somewhat motile in soil, and multiple strains occur in different crops.

Rhizobia play an especially vital role in the growth of legumes, a large group of plants that includes soybeans, peas, beans, peanuts, clover and alfalfa. Legumes are defined as having “pods that bear seeds” and generally have nodules that can symbiotically fix atmospheric nitrogen.

Digging deeper into the plant science

Rhizobial cells colonize young root hairs in the legume plants and create a natural symbiosis in the root tissue. Within two to four weeks of germination (the first trifoliate or V1 stage on a soybean), visible root nodules form. At that point, nitrogen from the air can become reduced/fixed in the plant and is then used to synthesize amino acids and proteins. Nodules become fully functional around the V3 stage.

How to check plant nodules

- Take a garden fork and gently loosen soil around the root system

- Gently lift the root system, trying to keep nodules intact

- Place root ball in bucket of water and carefully loosen soil to inspect nodules

- Note where nodules are located (near crown or on laterals) — location indicates activity, delivery formulation or delay in nodulation

- Note that nodule counts only mean so much, as different strains have different characteristics

- Carefully cut open nodules

Certain factors can affect rhizobial activity. These include the inoculant formulation itself; application timing; inoculant placement; hardiness of the rhizobial strain; weather conditions like air temperature, humidity and wind; plus the presence of pesticides and caustic fertilizers. Talk to your local seed representative to find out which factors you need to keep in mind.

With the right conditions at play, what started as a slurry applied on the seed becomes a dynamic interplay in the soil as the inoculant goes into action, delivering:

- Maximized nitrogen fixation

- Enhanced nitrogen availability

- Enhanced roots and root nodules

- Vigorous plants and plant health

- Greater plant health

So why inoculate if rhizobia live in the soil already?

For starters, rhizobial populations native in the soil tend to be inefficient nitrogen-fixers. Biological inoculants bring highly efficient rhizobia into the process.

Inoculation also provides nitrogen for the host legume plant in a form that’s highly cost-effective.

Effective inoculation not only leads to more uniform and strong plant growth, it also maximizes total yield by making its greatest contribution during critical bloom / early pod-fill periods.

For growers and the extended seed channel partners who are looking at ROI, inoculation offers an attractive return. In one example, Ohio State University in Columbus, Ohio, reported four times ROI on old rotated ground for soybeans.1

Ultimately, inoculants offer a beneficial environmental impact through reduced nitrogen fertilizer use, providing nitrogen credit in the soil for more than four years.

The BASF inoculant advantage

One of the leaders in inoculant research, innovation and production, BASF provides a robust offering to the agricultural industry that starts with highly efficient strains. Each strain is selected based on up to 25 years of experience from leading scientific institutions worldwide.

The company’s inoculant production is state of the art, incorporating the highest standards of sterile manufacturing.

Through its high level of professionalism — from product quality all the way through to supply chain management — BASF delivers on its promise of producing highly effective nitrogen fixation that results in crop yield and quality improvements.

One product that demonstrates the BASF inoculant advantage is Vault® HP inoculant for soybeans with its over-120-day on-seed survival. This solution has been shown to increase yield by an average of 2 Bu/acre,2 and it outperforms competitors 67% of the time.3

Inoculants are one part of a suite of integrated seed solutions for growers. From functional coatings and biologicals such as inoculants to insecticides and fungicides, BASF is helping to unlock the full genetic potential in each seed to enhance the performance of seed, seedling and plant for growers around the world.

How inoculants work

BASF

We create chemistry

www.agro.basf.com

1 Dr. Jim Beuerlein, Ohio State University, “Soybean Inoculation: Its Science, Use and Performance”

2 2009–2015, 282 University, Company and Independent Research Trials

3 2009–2013, 240 University, Company and Independent Research Trials