From the halls of Congress to the offices of the White House, biotechnology managed to get the attention of policymakers in Washington, D.C. this year.

In 2016, a GMO labeling law compromise was struck over the summer, proposed updates to the Coordinated Framework were announced by the White House and the Department of Agriculture continues their efforts to update and possibly expand their plant-based biotech rules.

It remains to be seen what impact these developments could have on the seed industry in the near future but with minimal dialogue on the topic at the national level until now, some consider any movement a step in the right direction toward a potentially less burdensome regulatory system. As policy gets developed and reviewed, the seed industry will watch intently to see if the dial moves toward more widespread acceptance or if the divide between transgenics’ proponents and opponents only gets wider.

The Latest Developments

Commodity groups, farm organizations and others considered the summer’s GMO labeling law a prudent compromise for what had become a divisive issue.

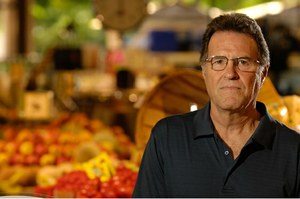

Kent Bradford, distinguished professor of plant sciences at the University of California, Davis, and director of the Seed Biotechnology Center, believes the legislation was passed to satisfy the food industry and they, as the end user, will be the biggest benefactor.

“It now locks into law that there is sharp division between biotech and non-biotech foods — a bright, white line — making it hard to normalize the use of these tools,” Bradford said.

“The food industry got the uniform law that they wanted that preempts state law…they just wanted the problem to go away. They are less uncomfortable with bright, white lines.”

How the United States Department of Agriculture decides to lay out these new labeling rules over the next two years, particularly if they choose to focus on product rather than process, will cement the bill’s lasting impact.

Bradford notes the irony that at almost the same time the labeling compact was being signed into law, another report was released from the National Academy of Sciences, stating that genetically modified foods posed no threat to human health.

“There’s no scientific reason for not using genetic engineering — 88 percent of scientists trust them but only 37 percent of the public. That’s a bigger gap than the climate change debate,” he said.

Karen Batra, director of food and agriculture communications for BIO (Biotechnology Innovation Organization), said the labeling debate helped raise the profile of other issues in the biotech space, such the need to streamline regulations.

“I think the debate over GMO food labeling helped to raise awareness of the U.S. regulatory system for biotech products, especially with policymakers. In addition, United States Department of Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack has testified before Congress at budget hearings, oversight hearing and general information hearings where the U.S. biotech regulatory system has been discussed and questions raised about the need for improvement in some areas, such as time frames,” Batra said.

Bradford says there’s nothing of substance in the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy’s Update to the Coordinated Framework for the Regulation of Biotechnology, released in September.

“There’s no real progress toward changing regulatory strategy or approach in these documents…it’s strictly about better coordination of agencies,” he said referring to those federal agencies that have jurisdiction over biotech products—the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

What Has Been Lost?

It’s impossible to know what economic benefits could have resulted from more genetically engineered crops coming to market in the last two decades, but it’s not hard for Bradford to quantify lost opportunities as enormous.

“Specialty crops haven’t had an opportunity to make use of these tools and so many things could have been developed, especially on the production side, when it comes to pests and disease. Those have been our major goals, in addition to nutrition and flavor,” he said.

The cause and effect in this situation are one in the same — it would be difficult to market new transgenic crops because so few have come to production and had the chance to gain acceptance.

“No one wants to be the one to get salad bars picketed. People want to justify the use of these tools with something new that will benefit consumers, but it’s more about getting people to just eat them,” Bradford said.

With limited opportunity to take these food crops to market, there’s not much interest from investors of any kind. Bradford notes that the evolution of computer and cell phone technology follows a time period nearly identical to transgenic crops, but each are now on very different paths thanks to private investment.

What Will be Lost If Changes Aren’t Made?

Another loss — also hard to measure — would be that of future talent. Does the next generation of plant scientists look at how government regulations have stifled genetic engineering potential and think twice about entering the field? The situation is certainly disappointing for students, many of whom see an opportunity to help people in developing countries through agricultural advancements.

“We do have a surge of enthusiasm for crop improvement. Right now we have more applicants that we can handle for our graduate program. These students see it as a way to have an impact globally by feeding the world,” Bradford said.

Students get into the program, and get to the research portion where many important concepts are often developed but, at that point, the reality sinks in that the barrier of regulation prevents that process from becoming a product. He likens the situation to using floppy disks.

Bradford points to the European Union, where even stricter transgenic regulations exist and, as a result, almost an entire generation of young scientists opted to come to the United States to work and study.

What the Future Might Hold

Batra said stakeholder groups like BIO are committed to stay engaged in the rule making process as the USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) works on amending the 7 CFR Part 340 regulations for biotech products.

“Some of the recommendations we have made include amending the regulatory process so that it’s more science- and risk-based and making the review process more timely and predictable, so seed developers are aware of the process and time frame going in,” she said.

If federal regulators have previously approved a herbicide-tolerant soybean, it should take them less time to review additional soybean varieties that come before them, particularly if they possess the same technology, Batra added.

Bradford said he’s optimistic that new, innovative breeding techniques will lift the industry over the hurdles they face right now. The USDA nabbed plant scientists’ attention when they said new gene editing technology like CRISPR falls outside of their regulatory realm.

“Companies have been sitting and waiting for regulations to change but now, I think, these new strategies will get them interested again in product development,” Bradford said.

“We hope now that this distinction between gene transfer and gene editing will hold up.”