A team of U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) scientists and their collaborators have established a strong link between honey bee health and the effects of diet on bacteria that live in the guts of these important insect pollinators.

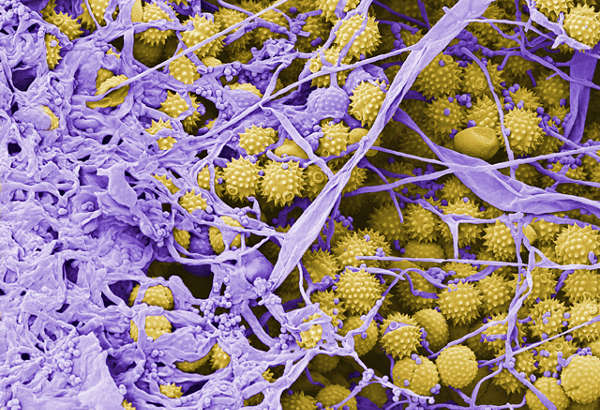

In a study published in the November issue of Molecular Ecology, the team fed caged honey bees one of four diets: fresh pollen, aged pollen, fresh supplements, and aged supplements. After seven days, the team euthanized and dissected the bees and used next-generation sequencing methods to identify the bacteria communities that had colonized the bees’ digestive tract.

The team also compared the thorax (flight muscle) weight and size of each group’s hypopharyngeal glands as measures of the diets’ effects on bee growth and development. The glands enable nurse bees to produce “royal jelly,” a substance that’s fed to developing larvae, ensuring the hive’s continued survival. The flight muscle weight represents the potential for work after the nurse bee transitions into the role of forager.

In general, bees given fresh pollen or fresh supplements fared better than bees given pollen or supplements that had first been aged for 21 days, reports Kirk Anderson, senior author and a microbial ecologist with USDA’s Agricultural Research Service (ARS) in Tucson, Arizona.

Bees fed fresh diets suffered fewer deaths, made better use of energy for growth, and had lower levels of gut pathogens such as Nosema ceranae, according to Anderson and co-authors University of Arizona graduate student Patrick Maes, ARS lab technician Brendon Mott, and Randy Oliver of Scientificbeekeeping.com.

In the study, the nutritional value of pollen lasted longer than that of supplement. Bees consumed significantly more aged supplement than aged pollen, but this didn’t translate into long-term benefits. For example, bees consuming aged supplement had plump nurse glands but suffered significant losses in flight muscle, suggesting that nutrition diverted to feed developing larva came at a significant cost to the bees’ own adult development. Poor development, in turn, can translate to early mortality or inefficient food collection when these nurse bees transition to the role of foragers.

Anderson says the effects of diet on gut bacteria populations (or “gut microbiome”) are poorly understood but warrant study because of the implications for honey bee health and the insect’s importance as a chief pollinator of 100-plus flowering crops. Put another way, consumers owe one in every three bites of food they eat to the work of honey bees and other pollinators.

Other key findings include –

- Bees fed fresh pollen or fresh supplements had more beneficial gut bacteria, like Snodgrassella alvi, whose presence was correlated with increased health, and decreases in gut pathogens Nosema and F. perrara bacteria.

- Five to eight types of gut bacteria were consistently found in bee gut.

- Dysbiosis was systemic, occurring throughout the honey bee gut.

Anderson says that with continued research, new supplement formulations or usage practices could be created to improve not only the health of honey bees but also the bacteria that live within them.

ARS is USDA’s principal in-house scientific research agency.