A Moment In Time

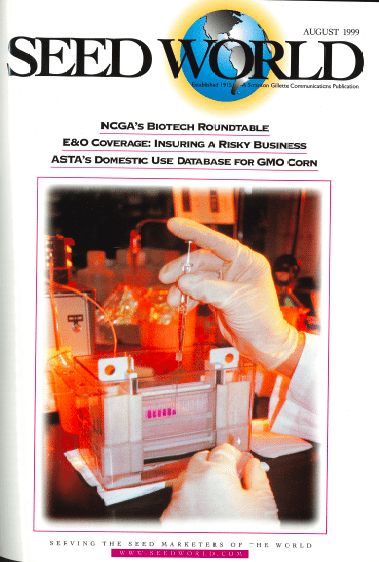

The cover of our August 1999 issue shows the process of analyzing corn protein using gel electrophoresis, “which is but one aspect of the biotechnology revolution sweeping the seed industry.” This edition covered issues surrounding GM products. In July of that year, U.S. agriculture secretary Dan Glickman addressed the issue of consumer acceptance of biotechnology in a speech to the National Press Club in Washington, D.C. “We need to examine all our laws and policies to ensure that, in the rush to bring biotech products to market, small and medium-sized family farmers are not simply plowed under. We will need to integrate issues like privatization of genetic resources, patent holders’ rights and public research to see if our approach is helping or harming the public good and family farmers.”

Facts and Figures from this 1999 Issue:

70 million is the number of bushels of U.S. corn sold to Europe in 1997. Sales would drop to 3 million bushels the following year.

$1.5 million is the amount of money used to kick off a fundraising campaign to build the Seed Biotechnology Center at the University of California — Davis in 1999.

95% is the amount of GMO corn planted in the United States in 1999.

42 is the number of member agencies that make up the Association of Official Seed Certifying Agencies (AOSCA) in 1999.

40,000 is the number of grain handling operations surveyed for the development of ASTA’s GMO corn purchasers’ database

Excerpts from this Issue

What if Consumers Don’t Love Biotech?

What happens if scientists, farmers and consumers do not love biotechnology as we hope they will? Speaking before the National Press Club in Washington, D.C., on July 13, Secretary of Agriculture Dan Glickman addressed this possibility in a speech titled, “New Crops, New Century, New Challenges: How will Farmers and Consumers Learn to Love Biotechnology and What Happens if They Don’t?” The following comments are excerpts of that speech.

“Biotechnology can help us solve some of the most vexing environmental problems: it could reduce pesticide use, increase yields, improve nutritional content and use less water.

But, as with any new technology, the road is not always smooth. In some parts of the world there is great consumer resistance and cynicism toward biotechnology. We have to ensure public confidence in general, consumer confidence in particular, and assure farmers the knowledge that they will benefit.

The important question is not do we accept the changes the biotechnology revolution can bring, but are we willing to heed the lessons of the past in helping us to harness this burgeoning technology? The promise and potential are enormous, but so are the questions, many of which are completely legitimate. We have to grapple with and satisfy those questions so we can fulfill biotechnology’s awesome potential.

To that end, I am laying out five principles I believe should guide us in our approach to biotechnology in the 21st century.

- An arm’s length regulatory process. Government regulators must stay an arm’s length, dispassionate distance from the companies developing and promoting these products, and protect public health, safety and the environment.

- Consumer acceptance. This is fundamentally based on the above regulatory process. Fundamental questions to acceptance will depend on sound regulation.

- Fairness to farmers. Biotechnology has to result in greater options for farmers. The industry has to develop products that show real, meaningful results for farmers.

- Corporate citizenship. In addition to the desire for profit, biotechnology companies must understand and respect the role of the arm’s-length regulator, the farmer and the consumer.

- Free and open trade. We cannot let others hide behind unwarranted scientific claims to block commerce in agriculture.”

After elaborating on these principles, Glickman concluded, “We need to examine all our laws and policies to ensure that, in the rush to bring biotech products to market, small and medium family farmers are not simply plowed under. We will need to integrate issues like privatization of genetic resources, patent holders’ rights and public research to see if our approach is helping or harming the public good and family farmers.”

Mixed Messages About GMO Corn Have Left U.S. Producers Confused

Just two years ago, U.S. corn sales to Europe were 70 million bushels; in 1998, sales dropped to only 3 million. Companies refuse to accept GMO corn products not approved for import by the EU. Still others reassure farmers not to worry about hybrids from their respective companies. What does this all mean?

While grain harvested from the vast majority of biotech corn crops in the U.S. has received import approval from around the world, some newer seed products, like hybrids exhibiting stacked traits, have yet to receive approval for import in the EU. Last summer, protests from consumer and environmental groups in Europe spurred more cautious treatment of U.S. GMO products by the EU. Now, with more stringent regulatory standards in the EU, companies are fearful of a mixture of GMO and non-GMO products, prompting decisions by some companies to reject all genetically modified products.

As a result, the U.S. corn market is experiencing a wave of paranoia. As a result, companies release statement after statement, instituting sweeping changes as to what they will and will not accept, leaving producers in a frenzy about what to do with their fall crops.

The American Seed Trade Association hopes to put an end to all the confusion. ASTA is helping launch a national database listing grain purchasers who accept biotech corn that has not yet received EU import approval.

Initial design functions include a local area search capability by zip code that allows growers to see a list of purchasers of non-approved grain in their specific areas. The database will also provide links to supportive associations and sponsoring companies. Growers who do not have access to the Internet will be able to access information from the database from most seed company representatives. The list will be compiled following a nationwide survey of about 40,000 grain handling operations to determine their willingness to accept approved and non-approved GMO products.

Rallying together in support of the database are AgrEvo, Garst, Monsanto, Mycogen, Novartis and Pioneer, six key players in the domestic and international corn market. Although the companies are in direct competition with one another, all say they recognized the need for a unified effort to deal with the GMO issues and provide assistance to growers.

Currently, four GMO traits found in U.S. corn products this year have been approved by the EU. Corn hybrids containing these approved traits represent a large majority — about 95 percent — of GMO corn planted in the U.S.

Hybrids containing traits not yet approved by the EU represent only 5 percent of corn grown in the country this year.