If I’m a smallholder farmer in sub-Saharan Africa, what questions or fears might cloud the merits of adopting soybean, a “darling” crop for development in the region?

“I’ve never even seen a growing soybean plant, nor have I seen a handful of harvested beans. No one in my family or the village knows much about soybean.

“I do know about the common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris), but I’ve been told the soybean is different. Neither my family, nor animals can eat the soybean, unlike the common bean. I’ve been told I can sell the harvested crop and collect money, but who will buy this bean that cannot be eaten?

“Is it wise to take such a risk? What if they don’t grow? Will I really be able to sell soybeans? What if no one wants to buy them or only for too little money?

“Because no one else in my village grows soybeans, where and how would I even obtain the seed for planting? Do I have the resources needed to purchase the seed? If so, how do I know what seed to buy and when to plant it? How do I determine the need for, and resources to obtain, other required inputs? Where would I get them and how do I learn to use them?

“If for any reason the new crop experiment should end in failure, will my family go hungry? Regardless of the outcome, how will I be viewed by my family and the community for having taken such a risk? Am I willing to tackle the task and shoulder the risk?”

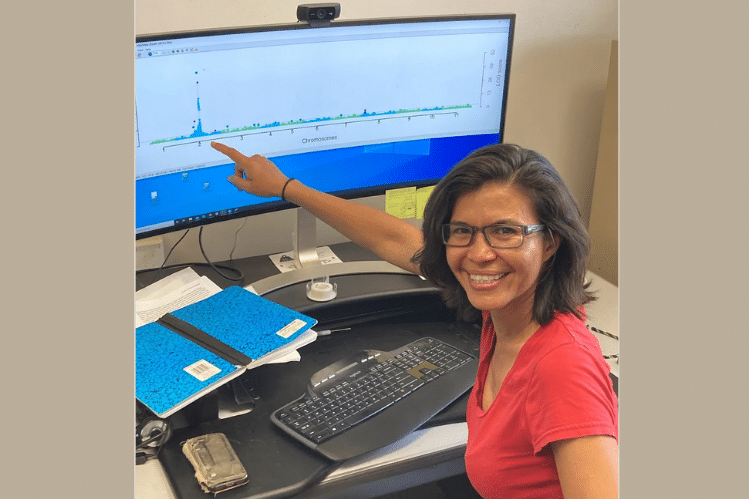

These are the thoughts and questions smallholder farmers ask themselves when new crops are brought into a region for the purpose of development, shares Krista Isaacs, a Michigan State University assistant professor, International Seed Systems, International Agriculture. At MSU, she’s been developing a research program, from which she can draw first-hand experience, designed to focus on Africa and Latin America.

The first time I met Dr. Isaacs, it was a chance encounter in Mali, West Africa, back in 2015. At the time she was a young scientist working on behalf of the International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics, commonly known as ICRISAT. Since then, I’ve reconnected with her back on U.S. soil.

When it comes to soybeans, she says development is being driven “through agricultural studies in the United States” versus taking a hands-on, in-country approach, which she recommends.

A self-described agroecologist, this former Fulbright Fellow has worked with multiple cereal and legume crops in Mali and the common bean in Rwanda. Furthermore, she has engaged in professional human nutrition work and studies in Bolivia and Uganda.

So, what is agroecology? Isaacs sums it up as the study within the realm of social and ecological components that influence, are influenced by, and act upon agricultural systems. She studies cropping systems, ecology and cultural aspects of farmer adoption of crops and varieties where farmers are both producers and direct consumers of crops grown.

As such, she adopts a social science-based approach. Isaacs considers an important aspect of working with smallholder farmers to be understanding the context, including the environment, gender and cultural norms, and socio-economic conditions in which they live and work.

Isaacs diverse background and expertise culminate almost perfectly to the field of agroecology. From the onset, her expertise has spanned critical areas such as farmer access to and the availability of preferred seed, participatory plant breeding, intercropping and crop ecology. Overlain with: knowledge systems, nutrition, gender analysis and qualitative research methodology.

To what areas might Isaacs’ science-based views of the discipline be applied to agricultural development initiatives? She identifies three: How do we maintain and develop diverse crops and varieties for niche environments? How do we build on existing (and successful) informal seed systems to ensure that improved and preferred varieties reach the communities that want and need them most? How do we empower people in the process of research so that they have new skills to continue on?

When Dr. Isaacs’ perspective is taken in account, intuitively supported and oft followed rationales for introducing new crop kinds bear questioning. A view from her back porch can be enlightening.