On February 27, 2020, the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) opened a new greenhouse at its research station in Tlaltizapán, in Mexico’s state of Morelos. The Garrison Wilkes Center for Maize Wild Relatives is named after a pioneering scientist in the field of maize genetics.

“The name teosinte refers to a group of wild relatives of maize,” says Denise Costich, manager of the maize germplasm collection at CIMMYT. “The seven members of this group — all in the genus Zea — are more grass-like than maize, produce hard-shelled seeds that are virtually inedible, and are capable of enduring biotic and abiotic stressors better than their crop relative.”

Teosintes must be protected, Costich explains, as they possess some desirable qualities that could help improve maize resilience in difficult conditions. Since CIMMYT’s Germplasm Bank is the global source for teosinte seed, the new greenhouse, designed exclusively for the regeneration of teosinte accessions from the bank collection, will ensure that there will always be seed available for research and breeding.

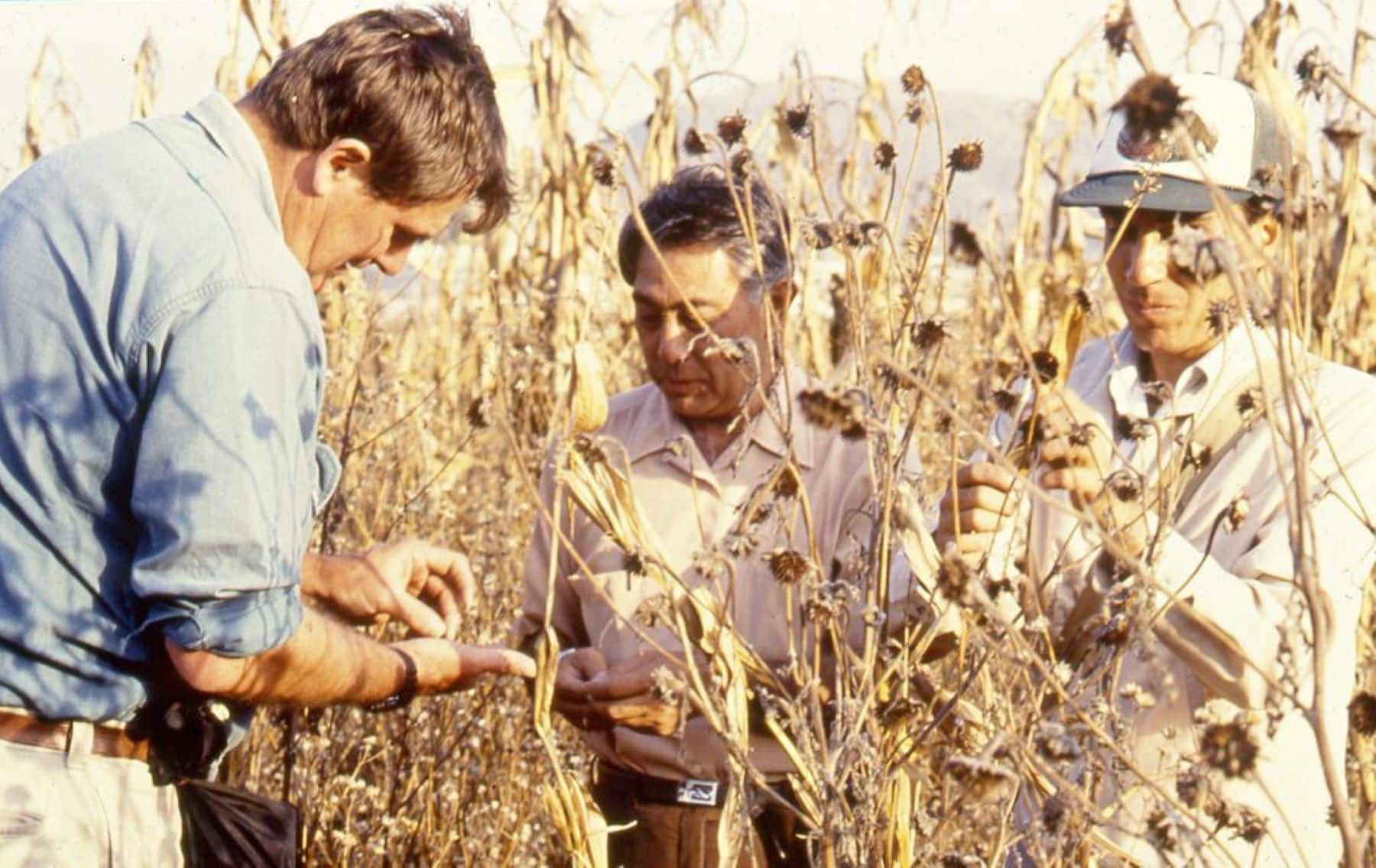

Garrison Wilkes was one of the first scientists to emphasize the importance of the teosintes and their close biological relationship to maize. He spent more than 50 years working on maize conservation in collaboration with CIMMYT. Together with scientists such as Angel Kato, a former CIMMYT research assistant and longtime professor, Suketoshi Taba, former head of CIMMYT’s Germplasm Bank, and Jesus Sanchez, as researchers at the University of Guadalajara, he contributed to the development of the global maize collection of CIMMYT’s Germplasm Bank as it exists today.

Keeping Seeds Alive

Teosintes are the wild plants from which maize was domesticated about 7,000 years ago. They are durable, with natural resistance to disease and unfavorable weather, and grow primarily in Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras and Nicaragua.

“What makes [teosinte] a wild plant is its seed dispersal. Corn doesn’t disperse its seed — it’s stuck on the cob. To be a wild plant means they can sow their own seed and survive,” explains Wilkes. Keeping these seeds alive could be the key to developing resilient modern maize with the potential to feed millions.

One of the difficulties in growing maize and teosinte in Tlaltizapán to produce seed for global distribution is that the station is surrounded by sugarcane fields. Sugarcane carries a disease called the Sugarcane Mosaic Virus (SCMV), to which maize and teosinte are susceptible, and SCMV-positive seed cannot be distributed outside of Mexico. Additionally, if teosinte and maize are grown in close proximity to one another, it becomes very difficult to control gene flow between them via airborne pollen. Several experiments, ranging from growing the teosinte in pots to monitoring that the maize and teosinte flower at different times, could not fully guarantee that there was no cross-contamination. Therefore, in order to continue to cultivate maize and teosinte within the same station, the CIMMYT Germplasm Bank needed to create an isolated environment.

On average, the teosinte seed collections in the germplasm bank were nearly 19 years old, and 29% were not available for distribution due to low seed numbers. Researchers needed to find a way to produce more high-quality seed and get started as soon as possible.

“My staff and I visited Jesus Sanchez, a world-renowned teosinte expert, and learned as much as we could about how to cultivate teosinte in greenhouses,” explains Costich “We realized that this could be the solution to our teosinte regeneration problem.”

Construction of the new greenhouse began in late 2017, with funding received from the 2016 Save a Seed Campaign — a crowdfunding initiative which raised more than $50,000. Donations contributed to activities such as seed storage, tours and educational sessions, seed collection, seed repatriation and regeneration of depleted seeds. With the new greenhouse, CIMMYT scientists can now breed teosinte without worrying about maize contamination, and prevent the extinction of these valuable species.

CIMMYT holds most of the world’s publically accessible collections of teosinte.

“The wild relatives are a small part of our collection, but also a very important part, as they are theoretically the future of genetic diversity,” says Costich.”They have been important in the evolution of the crop. If we lose them, we can’t learn anything more from them, which would be a shame.”

Source: CIMMYT