After a cut in demand due to the stay-at-home order, the ethanol industry is working on returning to normal.

As everyone has realized, 2020 has been a bumpy year for most industries. Industry demand has been shaken, businesses have closed … it’s overall been a hard year.

One industry that was particularly affected, though, was the ethanol industry.

In March, across the globe stay-at-home orders were enacted, asking and requiring people to not leave their homes for anything unnecessary. That meant going to work, going out to restaurants or even going to visit family halted. Most families only left home to go to the doctor or the grocery store.

And what did that mean for ethanol?

Stay-at-Home Means No Gas Usage

According to CoBank’s “Readjustment Today, Rationalization Tomorrow,” ethanol sector outlook, the U.S. ethanol sector experienced a catastrophic demand shock stemming from the reduced gasoline consumption.

“The way we’ve looked at the sector as the year began, ethanol production totaled to be about 16 billion gallons,” says Ken Zuckerberg, lead economist of grains and farm supply with CoBank’s Knowledge Exchange. “At one point in March and early April, that production was cut in half. At that point, we did a deep dive into where things were, where they were likely to go and what the industry would look like in the next few years.”

Economists at Purdue University saw a similar trend.

Farzad Taheripour, research associate professor in the department of agricultural economics at Purdue University, notes that the biggest factor into the decline in demand for ethanol production this year was certainly COVID-19.

“The demand for crude oil has sharply declined due to reductions in economic activities, which has led to a large drop in crude il prices,” he says, noting that from Dec. 31, 2019, crude oil fell from $61.14 to $14.10 in March 30, 2020.

Taheripour notes that in April, Purdue published a research report called the “Impact of COVID-19 on the Biofuels Industry and Implications for Corn and Soybean Markets.” In this report, he projected what the biofuels industry would look like after some of the effects of COVID-19 began to pass.

“Now, after several months from publishing that article, I can see that most of the things we projected in May actually happened over time since then,” Taheripour says.

He mentions that they were projecting that the demand for gasoline would drop 50-60% in April and May, and then it would gradually move back to normal towards the end of 2020.

“We were projecting that by the end of 2020, the reduction in demand for gasoline would be less than 10%,” Taheripour says. “Actual observations now confirm that the demand for gasoline in September was 9% lower than its level in 2019.”

In terms of actual data, Taheripour says the demand for gasoline dropped from 400 million gallons per day to about 200 to 250 million gallons in April and May, but as the restrictions and status of COVID-19 has changed, the demand for gasoline has gradually began to increase to more than 350 million gallons per day in September.

CoBank has seen a similar trend in their data.

“What we concluded in June was that these mass events — working from home, stay-at-home orders, the lack of mass events and the potential for an expanded recession — would cause the industry to recover to less than 90% pre-COVID production,” Zuckerberg says. “We’ve seen that recovery now to about 87%, and this is largely in line with our thinking. It’s sufficient to say that the rebound, which has been strong so far, will still take a number of years before we get back to anything that resembles normal life without a mask.”

Taheripour says he still expects another reduction in ethanol demand this year.

“My expectation is that we may see another round of reduction in gasoline demand,” he says. “Because of that, we may observe some reduction in demand for ethanol again towards the end of this year, as the cold season and flu season spreads and surges in the COVID-19 cases again.”

The average dry mill

ethanol plant produces:

2.9 gallons of denatured fuel ethanol

15.86 pounds of distillers for grains animal feed

0.80 pounds of corn distiller for oil for animal feed and biodiesel production

16.5 pounds of biogenic carbon dioxide for food, beverage and chemical manufacturing

Because flu season is still around the corner, Taheripour worries that there might be another COVID spike, causing a second round of stay-at-home orders that would negatively affect ethanol demand. However, overall, Taheripour believes there’s hope for the industry.

“As we move towards next year, if we have some kind of vaccines and treatments, we could expect to return to a more normal supply of gasoline use,” he says. “This could be a transitionary point in the market, however, and we need to have in mind the long term overall outlook for the ethanol industry.”

Drastic Industry Changes

Now, both parties expect to see some drastic changes within the ethanol industry to start meeting reductions in demand.

Zuckerberg notes that one major thing on the top of his mind right now is the excess capacity of ethanol that was there prior to COVID-19.

“We began 2020 with about 1 billion gallons of excess capacity,” he says. “Now, we expect that excess capacity to be in the double digits.”

But what does that mean for the industry? Zuckerberg says there might be consolidation.

“There’s a lot of ethanol plants out there who can’t make the profit,” he says. “Consolidation is likely. If that happens as we believe it, that could benefit the strong players that are a bit more technologically savvy.”

He notes as well that even though we’re only back up to 87% of ethanol production, margins still look good.

“Those technologically savvy players are being efficient, and that’s giving us a pretty good margin in the industry today,” he says. “It kind of goes under the phrase ‘When life gives you lemons, make lemonade.’ When you can manage the production, make lemonade.”

However, in the future, both Taheripour and Zuckerberg believe there will still be some factors that could shake up ethanol demand — and it’s not COVID-19 related.

“One of the long-term effects to ethanol in general is creeping up on us,” Zuckerberg says. “Electric vehicles. That’s going to create some pressure on U.S. ethanol.”

“The existing evidence is showing demand for gasoline in the United States will not grow significantly in the future,” Taheripour says. “The reason it could go down is because of the improvement in the efficiency of new cars and the movement towards more electric cars. That would create less of a demand for gasoline.”

Zuckerberg says currently, CoBank is only seeing about a 6-7% penetration of electric vehicles to be likely by 2026.

“This is a manageable situation,” he says. “If we think into the future by 2030, that would only bring the uptick of electric vehicles up to maybe 10%, and I do think that might be likely.”

But, Zuckerberg mentions this is a good timeline for the ethanol industry to be able to appraise the situation and regroup.

“One idea is possibly to have a more diverse product offering for the U.S. corn crop,” he says.

Currently, about 30% of U.S. corn crop is dedicated to ethanol.

“Diversifying seems like a no-brainer to us,” Zuckerberg says.

However, both Zuckerberg and Taheripour note that there’s one place the industry could benefit: a higher blend of ethanol in gasoline.

“Traditionally in the United States, we try to use a 10% blend of ethanol in gasoline,” Taheripour says. “So, with that tradition, if the market for gasoline grows in the future, of course we can have more demand for ethanol.”

However, Taheripour notes that doesn’t seem to be the current case in terms of ethanol demand.

“Existing evidence is showing that demand for gasoline will not grow significantly,” he says. “As a result, if we wanted to just stay with the 10% blend, this means that the demand for ethanol will fall.”

Zuckerberg echoes this sentiment.

“If states approve a higher blend rate of ethanol, that’s a demand driver,” he says.

“Higher blending rates for ethanol — either 15% or 20% — would generate more demand for ethanol, which would make sure we secure a demand for corn ethanol,” Taheripour says.

Brazil’s Looming Competition

Another long-term factor also looms in the distance — a competitor who could give the United States a run for their money in terms of ethanol production.

“Demand for ethanol is beginning to be torn into competition between the United States and Brazil,” Taheripour says.

Traditionally, Taheripour notes that Brazil’s ethanol production comes from sugarcane. However, more recently, that is beginning to change.

“Brazilian farmers are now producing more and more corn in combination with soybeans, due to the benefit of a double cropping system,” he says. “This means that each year, they’re able to use their land twice: once for corn, and once for soybeans.”

With this new technology, that means Brazil is rapidly increasing its production of corn.

“Traditionally, Brazil isn’t a large producer of corn,” Taheripour says. “But they’re going to become a larger corn producer, and soon, an important market for Brazilian corn would be corn ethanol production.”

“Brazil has been a No. 2 producer of ethanol fuel,” Zuckerberg says. “When you think of who’s selling what to China, that’s one of the countries we’ve got on our brain.”

While Brazil still imports U.S. ethanol, Zuckerberg notes that it could become a formidable export competitor because of its trade access to China.

“Brazil’s ability to be more cost competitive is challenging the United States’ long-term aspirations to increase ethanol exports,” he says.

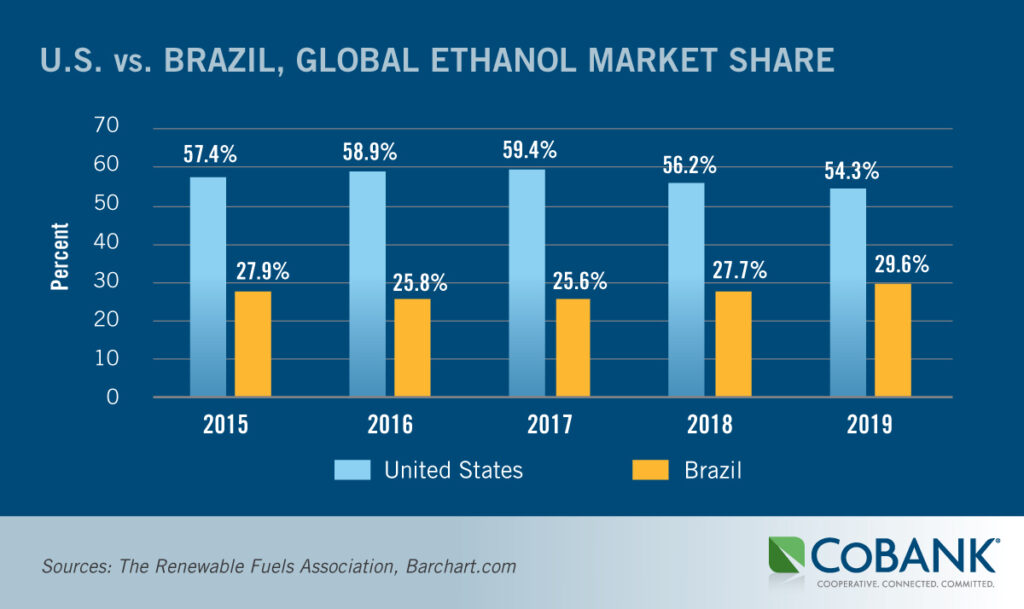

According to Zuckerberg’s report, in 2019, world ethanol production totaled 29.1 billion gallons, with the United States and Brazil accounting for 84% of production. Brazil, however, has been growing production faster than the United States over the past five years, averaging about 5.2% vs the United States’ 2.0%.

“The result is an incremental increase in market share for Brazil and decrease for the United States during this period,” he says.

All-in-all, Zuckerberg says it’s time to watch.

“Whether or not Brazil will overtake us as China’s most important ethanol exporter is imperative to know for the U.S. ethanol industry,” he says.

The final part Zuckerberg notes to watch in ethanol’s future is commodity prices.

“Wouldn’t you know it, China is actually buying corn, soybean and sorghum, and in the last few months, we’ve seen a big pick up in corn, soybean and sorghum prices,” Zuckerberg says. “Corn is a feedstock for ethanol, and higher corn prices are a welcome to the U.S. farmer. However, that requires higher prices from ethanol producers.”

Zuckerberg says to think of a pizzeria — if the cost of cheese and flour go up, what will happen if you don’t adjust your prices? You’ll go out of business.

“Farmer margins are low and that’s good, but if corn stays high, we’ll have to see ethanol fuel prices go up,” he says. “We are hugely focused on what’s happening with corn prices, and how that will affect the future of ethanol prices as well.”