‘Regenerative Ag’ might be the new trending phrase, but the meaning goes back to the beginning of agriculture.

It’s hard to open an agricultural publication these days without reading the words “regenerative agriculture”. The words are new, but the practices are as old as agrarian civilization. The concept is easy — work with nature rather than against it. The management practices, on the other hand, can be as diverse as the farms that implement them.

The premise of the movement values soil health above all other components of the production agriculture equation, allowing that soil health is the foundation for every possible throughput and output.

During her career as a Research Soil Microbiologist for the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), Kris Nichols spent more than 14 years working directly with farmers in central North Dakota.

“North Dakota was one of the first places that regenerative agriculture started. One of the main reasons it started in that area is because of the extremely stressful environment, which also made for stressful financial margins,” Nichols says.

Many of the farmers Nichols worked with practiced crop fallow, a practice that saw a cash crop planted on year one and the field lie barren on year two. The fallow is implemented through chemicals, with the thought being that a fallow year would store moisture and nutrients for the next year’s cash crop. Essentially, farms had to make enough money in one year to sustain for two.

As Nichols’ work in the area grew, she began to work with farmers to implement new cropping strategies where the soil was never without a managed cover. The science-based trial and error was the foundation for what would become known as regenerative agriculture in the United States, and helped those who ascribed to the practices view agriculture through a

different lens.

“I would always tell the farmers I worked with in North Dakota that they were growing soil. The crop they were growing, the livestock they were placing on the crop, those things are just tools to help grow better soil. And, for me, that is the heart of regenerative agriculture… regenerated soil.”

Leveraging the experiences she garnered through her work with North Dakota farmers, paired with a PhD in soil science and her holistic view of the modern production agriculture paradigm, Nichols is regarded as a pioneering thought-leader on regenerative agriculture.

The Basics

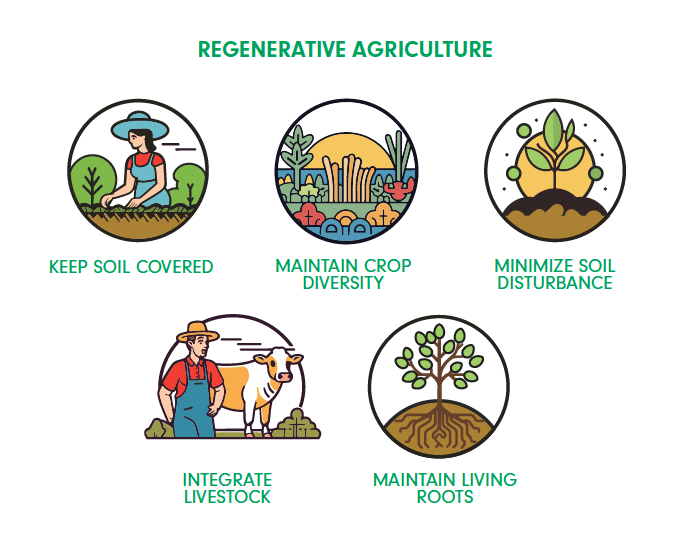

Regenerative agriculture operates in multiple ways to produce a soil health benefit. A systems approach that relies on the adherence to principles rather than certifications and prescriptions guides regenerative agriculture implementation.

The approach hinges on keeping soil covered, minimizing disturbance, integrating a variety of plants to diversify life above and below the soil’s surface and the incorporation of animal, both macroscopic and microscopic.

“When I talk about integrating animals, it doesn’t mean that everyone has to have a grazing animal,” Nichols says. “What it means is that you need to be thinking about the insects and the microscopic animals as well as the wildlife.”

And implementing the system is not an all or nothing approach, and “context” is an operative word that those looking to begin their journey in regenerative ag will hear frequently.

“Regenerative agriculture was started by farmers who had questions and wanted to see if there was a different way of doing things on their individual farms. They needed to make changes because of the stress level in their farming systems. And I think there’s a lot of interest in regenerative agriculture today because food production, at all levels, is under a lot of stress. But there’s no one recipe to get there,” Nichols says. “Just like baking a cake is different if you’re on the Atlantic coast; you can’t just follow a recipe card. You have to respond to where you are and what’s going on around you. Regenerative ag is the same. You have to be able to respond to weather projections, crop prices, and consumer demand. Regenerative ag allows you to have that dynamic response.”

Every farm is unique in its soil health starting point, long-term goals and available human, equipment and financial resources. But all can agree that any implementation is better than no implementation.

The Bottom-Line

In southeast Iowa, Mitchell Hora is the seventh generation to farm his family’s land, a responsibility he doesn’t take lightly.

The Continuum Ag founder and regenerative agriculture champion is leveraging the ag conservation leadership that has always been a part of his family’s farming operation with his ambition to help farms around the world achieve soil health through regenerative practices.

“The conservation side of things has been ingrained for a really long time, and, I think, that’s why we’re at the spot that we’re at,” Hora says. “Dad started using no-till in 1978 and we’ve been using cover crops since 2013. Washington County, where we’re at, has a long history of conservation farming. We’re all trying to push the envelope and drive further. For us, it’s about making money and we’re using the cover crops and the no-till in these conservation systems as offensive management tools. They’ve got to drive dollars to our bottom line.”

Hora says that on the 700 acres that makes up his family’s farming operation, every decision and every action must be profitable.

“We have to be profitable now, we can’t wait,” he says.

Today, soil biology is the driver of both Hora’s on-farm and entrepreneurial business models.

“Soil is very biologically driven and it’s the biology that’s going to help you manage your fertility,” he says. “It’s not us as caretakers of the land. We’re actually farming those microbes, those microbes know how to farm a crop way better than we do, and now with the Haney test, we’re able to understand how to better farm microbes.”

Through the Haney test — which provides a test and gauge of the biological activity occurring in the soil, proprietary soil health software and a network of soil health experts — Continuum Ag works to equip farmers in 36 states and 14 countries with the knowledge and resources they need to better farm the microbes that farm their crops.

“Our goal is simple,” Hora says, “We want to implement the principles of soil health and manage fertility to protect yield on a year-to-year basis. We want to make sure that a farmer is going to have success economically and understand the logistics of how to get there successfully.”

Scalable Fundamentals

Today, Nichols serves as the principal scientist and research director for MyLand, a company approaching soil health as a service. Sans a product and equipment, the company allows a farmer to supercharge the naturally occurring microalgae present in their soils and implement the technology across their acres without significant changes to their farm’s infrastructure. The model works by extracting native organic microorganisms directly from a farm’s soil, rapidly reproducing them and then delivering those live microorganisms back into the same soils they were extracted from via irrigation.

“What we’re doing at MyLand is exciting because of the acceleration it provides. We’ve been taught through academia that it takes a 1,000-years to develop an inch of topsoil. We know now that we can do it much faster, so that a farmer can benefit in their lifetime, and biologically based tools are one of the ways we get there,” says Nichols.

And there’s plenty of interest in supporting and enhancing soil biology. According to Fortune Business Insights, the global agricultural biologicals market size was valued at $7.42 billion in 2018. By 2026, that value is projected to reach $20.59 billion.

And companies are getting creative in how they deliver those biological advantages. It doesn’t get much more simplistic than using graphite to lubricate seed in the planter box, a fact Verdesian Life Sciences is leveraging.

With their SEED+ technology, Verdesian is also giving both organic and conventional farmers alike, the opportunity to try biostimulants without any modifications to their existing system.

Mike Canady, has spent his career developing plant resilience through both traditional breeding and soil microbiology pathways. Today, Canady serves as the director of agronomy, specialty crops for Verdesian. Canady says that the adoption these technologies are seeing is nothing short of exciting.

“We’re seeing it mostly adopted in conventional corn and soybean cropping systems, even though it is certified for organic production. I think a lot of that is due to the fact that it is an economical product, it really delivers a lot of cost and time efficiency for any type of production.”

These regenerative solutions and the many more in the pipeline couldn’t come at a better time. The push to steer agriculture down a more holistic road has never been greater, and the brunt of those demands seems to be landing squarely on the shoulders of the farmer. But Nichols says that there is hope. For farmers, for the soil and for the climate.

“Part of the hope in soil regeneration is not to force farmers into practices but to provide them with opportunities and options to address their bottom line as well as climate change.”