The first of five entries in our Pillars of Professionalism series, profiling people and the skills they’ve mastered to help teach you skills for success in today’s seed industry.

Personal connections are crucial in business, says Dilantha Fernando, Dean of Studies, professor, plant pathologist and epidemiologist at the University of Manitoba. He’s considered a mentor to many in the plant pathology community, having trained over 75 graduate students and postdoctoral scientists at the university and another 68 undergraduate students.

He’s also known as one of the plant breeding community’s true facilitators, someone who can get people around the table and to work toward a common goal. It’s a skill that saved the canola industry billions in revenue a number of years back, and a skill he comes by after an experience he had in his teens in Sri Lanka where he grew up.

“When I was 15 or 16, I started to give private tutoring lessons to students younger than me who were pursuing a high school diploma. That really taught me that I had the potential to train people and for them to be successful,” he says.

The confidence he gained from helping others advance helped him build a successful career that brought with it other opportunities to help others advance professionally.

“I was very fortunate at the beginning of my career to have some of the best students who are now doing a lot of good work in the industry, in academia and in provincial government.”

That cohort has accomplished some amazing things, like bringing the industry together to solve a problem it faced in 2009 when China stopped importing Canadian canola due to a blackleg issue.

“The amount that was going to be lost to Canada was estimated at $3 billion each year. Of course, we knew there were likely political reasons for it, but I saw it as an opportunity as a researcher.”

With a lot of help, Fernando and his team took on a project to identify resistance genes that were available at the time in Canadian canola varieties. It led to the modern system of labelling them with a letter of the alphabet. Seed companies are now able to tell buyers exactly what resistance genes are in a certain variety.

To do that, of course, he needed to get people into a room. That was only possible through drawing on his network and then leveraging those partnerships to get the job done. Immense help from the Canola Council of Canada to implement the labelling system came through due to the many scientific presentations he and his colleagues gave on this subject.

“That’s a big thing and can be difficult to do. There are a lot of seed companies involved in canola, and they have their own intellectual property. We had to make sure that we didn’t break any of those rules,” he says.

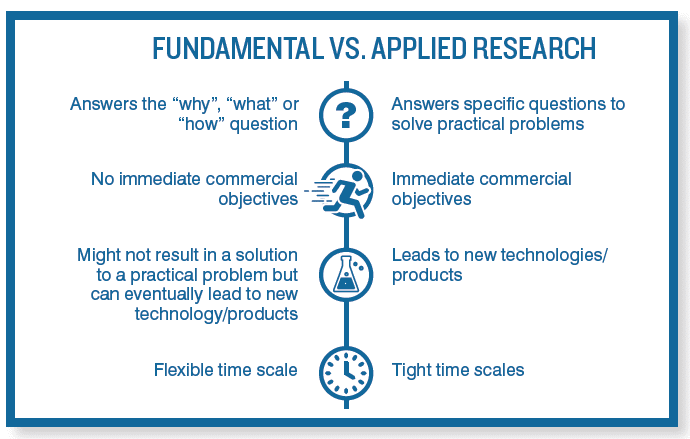

He says the plant pathology/ breeding community is very tight-knit and those involved in it know what their research is good for — fundamental and applied research are very different and have their own strengths and weaknesses.

“Breeders and plant pathologists are always working together. We can come together when need be and figure out how to get the job done.”