Now a half-century old, Canada’s national gene bank system continues to play a vital role in preserving the genetic diversity of essential food crops.

This year marks the 50th anniversary of Canada’s national gene bank system, known as Plant Gene Resources of Canada (PGRC), which was established to preserve the genetic diversity of cultivated crops, their wild relatives, and native Canadian plant species for food and agriculture.

Axel Diederichsen, research scientist and curator of the PGRC, says the federal government’s decision to create a national, centralized seed bank in 1970 was a reflection of the times.

“In the late 1960s, many countries around the world started to realize how important genetic resources were for agriculture and food production,” says Diederichsen. “Because a lot of genetic diversity was disappearing, they realized that it was very important to preserve it.”

Diederichsen notes that back then, numerous seed collections were held here and there by public and private plant breeders in various locations across Canada, but there was growing concern about what would happen to all this material in the event of retirements and other circumstances which could leave some valuable collections orphaned with no place to go.

“How do you preserve these materials? You need to have an active gene bank that can maintain them and grow it out and make sure that you have viable seeds to distribute,” he says.

Diederichsen is a staunch believer that germplasm preservation is vital for the continued sustainability of agriculture.

“There’s been many changes over the last 100 years during the industrialization of agriculture,” he says. “A lot of the diversity that we have at PGRC or in other gene banks around the world would have been lost if we didn’t have these genetic resources.”

Bryan Harvey is an emeritus professor at the University of Saskatchewan who was appointed to the Order of Canada for his outstanding achievements in barley breeding. He served many years on the Canadian Expert Committee on Plant and Microbial Gene Resources and was a strong proponent of a national seed bank at the time the PGRC was established at Agri-Food Food’s Central Experimental Farm in Ottawa in 1970. His barley variety CDC Copeland, which dominates the brewing world, won a Canadian Plant Breeding Innovation (CPBI) award earlier this year.

Harvey recalls that in the beginning, the seed bank was run on a shoe-string budget and only had two staff members, a curator and a technician, who worked out of a re-purposed garage on the farm.

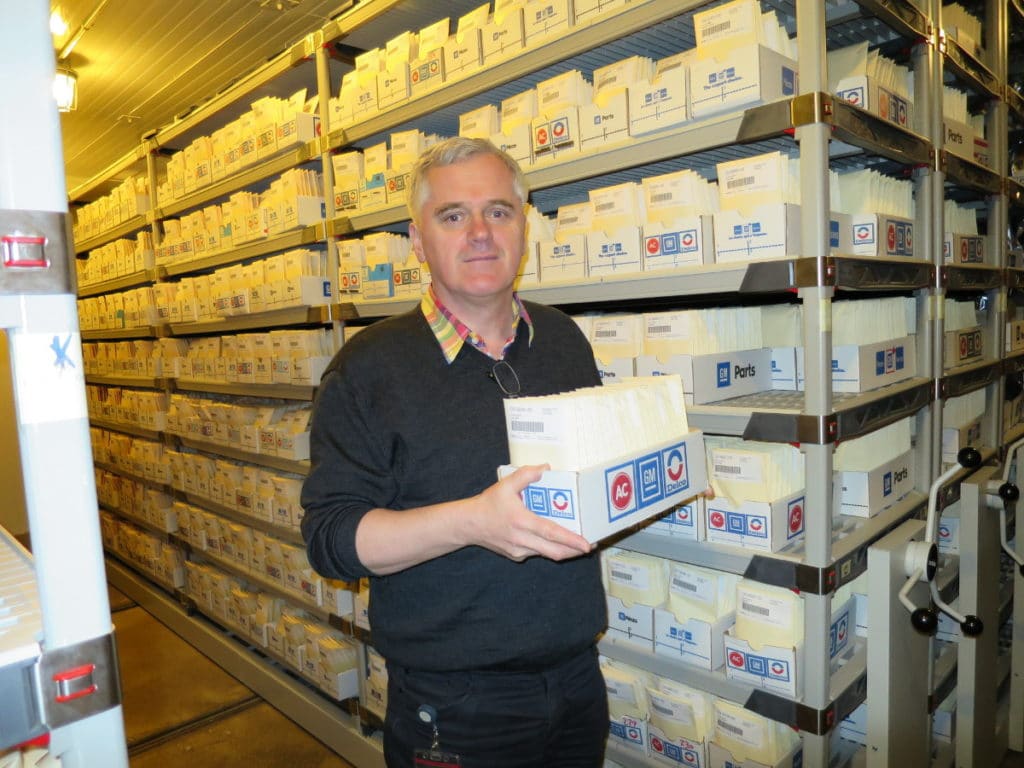

“They had all these envelopes which contained the seeds, and they needed something to put them in. What they used was Delco Spark Plug boxes that happened to be just the right size for doing that,” Harvey laughs.

“It’s funny now, but that’s where it started,” he says. “Now, we have a world-class facility in Saskatoon, and we’ve certainly gone way beyond those Delco Spark Plug boxes to store the materials.”

In 1998, PGRC moved to a brand-new facility at AAFC’s Saskatoon Research and Development Centre, which is located at the University of Saskatchewan campus.

Harvey remembers the move from Ottawa to Saskatoon well. He says that as insurance against precious genetic material being lost or damaged due to accidents or other unforeseen circumstances during transport of the PGRC collections, each seed sample was split in two.

“One half was sent out by truck, and for the other half they decided the Royal Canadian Air Force should fly it out,” says Harvey, recalling there was a fair amount of publicity about this at the time.

Today, the Saskatoon facility is the primary seed repository for PGRC, holding the bulk of the seed lots referred to as accessions for cereals and other crops. There are two other gene banks in the system as well. The Canadian Clonal Genebank in Harrow, Ont. stores germplasm for fruit tree and small fruit crops, while Fredericton Research and Development Centre in New Brunswick is the repository for potato germplasm.

According to Diederichsen, the number of seed samples stored at the Saskatoon gene bank has expanded enormously since the PGRC’s inception. Currently, it holds approximately 115,000 different accessions, of which 70 per cent are barley (40,000 accessions), oat (28,000 accessions) and wheat (13,000 accessions).

Diederichsen says the reason why so much space is dedicated to barley and oats is that under reciprocal arrangements the PGRC has with other gene banks around the globe, Canada has been designated to maintain the world base collections of those two field crops.

He adds that much of the genetic material was collected by Canadian scientists travelling abroad to find promising seeds that could be used to benefit wheat, barley and oat breeding in Canada and other countries, something that continues to this day.

“They went to the Near East, to North Africa, to the Mediterranean, on expeditions to bring this material back, including many wild species,” says Diederichsen, noting that much of what’s in the PGRC seed bank has and continues to be contributed and utilized by other nations as well.

Diederichsen points out that apart from cereals, genetic material for many other noteworthy crops can be found there, too.

“We also have interesting collection of some oilseed products like rapeseed and brassica oilseeds, and there’s an important collection of forages here in Saskatoon as well,” he says. “For these crops, I would say we’re among the world’s leading gene banks. But then we have some germplasm for many other smaller crops, too.”

Diederichsen reports that each year, more than 5,000 accessions are shipped out to scientists in Canada and around the world who utilize the material in their research and plant breeding work.

“That’s been the average through the last 15 years, but we’ve had some recent years where we shipped close to 10,000 seed samples to clients, with about 30 per cent going to other countries,” he says.

Diederichsen notes that a primary objective of the Saskatoon gene bank is to generate high-quality seed, something that’s done at the facility’s fields or greenhouses or with the help of collaborators in different locations.

“We try to produce seed of good quality to start with, because it doesn’t age as quickly and will store better over a long period of time,” Diederichsen says. He adds that PGRC scientists and technicians will also evaluate, describe and perform genetic analysis on accessions that can be passed on to plant scientists utilizing the material.

Diederichsen says storage space at PGRC’s base in Saskatoon is in very tight supply nowadays, and as a result, several things are taken into account when deciding what can go into the seed bank and what can’t.

“The central consideration is that we must be able to regenerate it and also ensure that we can preserve it properly,” he says. “That means we have to prioritize, and we have to decide where we use our limited resources,” he says.

“We are at capacity right now,” Diederichsen says, noting there are plans in the works to expand the storage facility eventually. “Every year, we add maybe 500 accessions, something like that, but our collection is growing much more slowly now than during the first years.”