Sustainable Development Goal No. 17 focuses on global partnership for a stronger food supply, which is a key part of the International Year of Plant Health.

The global food system is highly complex.

It relies on multiple elements and actors: seed, soil, water, technology, farmers, traders, retailers, regulators, consumers and many more. Seed is at the beginning, the primary input to all food production. Healthy soils, meanwhile, sustain all biological activities on the planet. And of course, none of this would be possible without the farmers who grow the crops. At the same time, the policies in each country determine how all of these activities take place. With all these moving parts, one might wonder if the various pieces of this vast agricultural community are moving in synchronicity, driving towards the same goals.

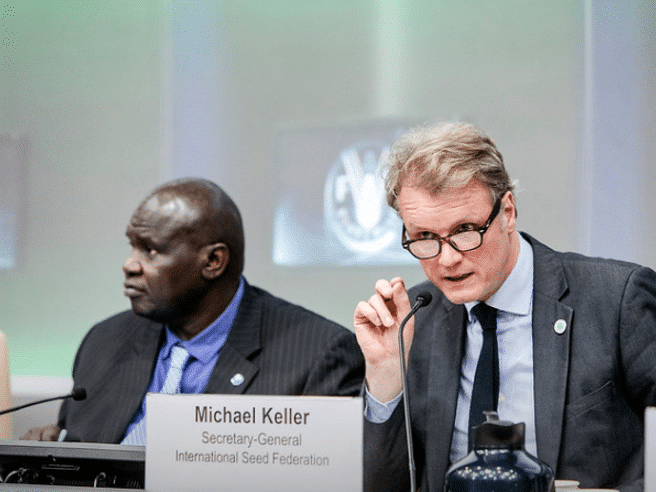

Michael Keller, secretary general of the International Seed Federation (ISF), believes this is precisely the reason why the seed sector must engage. Seed is just the starting point, but to build a well-functioning food system, all the other perspectives have to be taken into account because they are the key to answering many of the problems we face in feeding the world.

“We have great diversity of views, but the goals are the same in many ways,” Keller says. “In the end, we all have one goal in common and that is sustainability itself. We have to produce more with less and in a sustainable manner.”

The United Nations General Assembly declared 2020 as the International Year of Plant Health and in doing so, the International Plant Protection Convention helped outline seven of the UN Sustainable Development Goals to go along with the year, including No. 17: strengthen the means of implementation and revitalize the global partnership for sustainable development.

Ultimately, the goals are to boost economic development, protect the environment, reduce poverty and end hunger, all by protecting and promoting plant health.

“We have to accept this is something we have to do together,” Keller says. “That’s the most important thing. Nobody can achieve this alone. There is a wealth of expertise around us and many groups representing different areas of focus. We must actively engage.”

Mark Watne, president of the North Dakota Farmers Union (NDFU) and representative of the World Farmers Organization (WFO) for the World Seed Partnership (WSP), says efficiency is at the heart of collaboration.

“When you’re having these discussions, if you don’t include the farmers, the laboratories, the promoters, the seed storage systems or other groups, you may find each of those groups’ goals aren’t completely aligned with the other groups that need to use those resources down the line,” Watne says. “You get a much better end result, and you get it quicker and more efficiently.”

World Seed Partnership

The World Seed Partnership (WSP) is one such collaboration, with the goal of providing food security through sustainable production in the context of population growth, urbanization and climate change.

Created in 2017, this initiative is made up of The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the International Union for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants (UPOV), the International Seed Testing Association (ISTA), International Seed Federation (ISF), and the World Farmers’ Organization (WFO); five international organizations coming together to support the development of the seed sector in countries around the world.

“When you’re really trying to solve an underpinning problem of quality seed, it takes a lot of people and folks with skin in the game to get to that end result,” Watne says.

UPOV focuses on the establishment and implementation of an effective system of plant variety protection while ISTA comes from the background of enhanced seed quality assurance for better on-field performance through improved seed sampling, seed testing and storage capabilities.

OECD is concerned with the development of a reliable and internationally acceptable seed varietal certification system for seed movement nationally and internationally.

ISF works to facilitate growth of the local seed industry to ensure farmers’ access to improved varieties and seeds, while WFO ensures farmers are participating in relevant discussions and helps maintain access to new plant varieties and sustainable and affordable seeds.

“I think we’ve been working on these things but not working together as well, at least we weren’t all as focused on the highest priority goals,” Watne says.

Proof in the Progress

Making quality seed available for all farmers is a challenging goal, but the World Seed Partnership has seen positive outcomes in several countries already. The United Republic of Tanzania was the first success story. It is now a member of UPOV, has a national seed testing laboratory accredited by ISTA, is a member of the OECD Seed Schemes and has strong national seed and farmers’ associations in place.

In 2019, the WSP organizations participated in a seed-focused Congress in Nigeria where stakeholders from the political and agricultural sectors came together to promote change. Nigeria also now has an ISTA seed testing laboratory and is an observer country to the OECD Seed Schemes. There has been progress in Ethiopia and other countries, as well.

All of these are significant efforts, but Keller says the progress can be difficult to see because so much of the work is done behind the scenes.

“In order to provide seed choice to a farmer in Africa, the supply chain has to be in place first,” he says. “We need to be able to develop locally adapted varieties, produce the seed, ensure its quality, and have the right set of regulations in place for a seed company to get its products to farmers, who must then have not only the finances available but also an understanding and appreciation of the value of buying quality seed.”

Cooperating with local non-governmental organizations (NGOs) is critical.

Some of the biggest challenges involve showing farmers the benefits of using improved seed and training them on modern agricultural practices. There are many organizations working on these problems, including the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, Fair Planet, as well as public research institutes and even private seed companies.

“Some of these farmers have never seen an improved variety of seed, so having those test plots with trials, where farmers can come and see the difference, allows them to see four to six times the harvest,” Keller says.

Both large and small farms benefit from these efforts.

“At WSP, we don’t get in depth about how farms should look,” Watne says. “But we do need to find the best avenue to produce enough food to sustain ourselves as the population grows, or furthermore, to feed the people we currently have, and a lot of that is going to depend on the seed.”

Other Organizations

The Soil Health Partnership (SHP) is a farmer-led initiative of the National Corn Growers Association with over 100 partnerships in place to evaluate the agronomic, economic and environmental impacts of adopting soil health practices on working farms.

“Farmers in SHP’s network work with SHP field managers to design and test research on soil health management practices, such as no- or reduced-tillage, cover crops, and nutrient management in advanced soil health management systems,” says Stacie McCracken, communication lead for Soil Health Partnership.

With such extensive partnerships in place, SHP has experience in working across company borders.

“The SHP network has expanded to 220 sites in 16 states, ranging from Maryland to North Dakota, from Minnesota to Florida,” McCracken says. “Efficiencies can be gained when you are working together. You can build upon each other’s work to make stronger movement forward.”

The Climakers, a farmer driven climate change alliance, is another good example of a large number of groups working together. The website lists 14 organizations, private associations, universities, research centers and media partners that have joined forces with the goal of enhancing the position of the farmers in the global political discussion on climate change.

ISF is one of the founding members of the alliance. Recently the Climakers participated in the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change COP25 in Madrid, together with the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) Centre for Climate Change, Agriculture and Food Security (CCAFS) to lead a discussion about transforming food systems with a farmer-driven climate agenda.

Keller sees efforts like this as being crucial to success in partnerships that will bring about lasting sustainability progress.

“The farmers have to be there. They are key in making these changes,” Keller says. “Farmers are vulnerable to climate change, but they are not a passive actor. They are executors of change and can offer plenty of solutions too.”

Building Blocks of Trust

Just because companies and organizations are working together more often, doesn’t mean the business side of things has lessened, but rather the trust has grown.

“We are doing business, that’s not something we need to hide, but we want a sustainable business model, not just for us, but for those we are selling seed to,” Keller says. “If a farmer uses a particular seed and it fails, he will lose money, and not work with that seed company anymore. Just because we are doing business, does not mean we are not working together.

“In the past, the seed sector didn’t really speak out and join those conversations,” he says. “It was more about protecting what we may know, and others were guarding their perspectives as well. We’re starting, more and more, to be integrated. It’s not enough for seed to be a silent contributor.”

Watne says it is worth it to put in the extra effort to establish structure, communication, priorities and operational tasks in the early stages of a partnership.

“There are going to be logical challenges with meeting times and language barriers, and approval procedures, but those things aren’t burdensome once you’ve established the process and have a good group to work with,” he says.

McCracken agrees the beginning stages of a partnership are critical to its success.

“Whether you are deciding how to make lunch or how to increase the soil’s organic matter, ideas are never in short supply when you bring people together. It is important to identify goals and purposes up front to create an environment for all organizations and ideas to flourish,” she says.

A Better Balancing Act

As seed companies, farmers and other agricultural organizations realize the benefits in partnering to reach bigger goals, more collaborations have sprung up. While it can be tempting to work with every opportunity that exists, McCracken says it’s important to find partnerships that have a focused purpose.

“There are many groups working on these issues. While we believe there is great power in partnerships, stay active in partnerships that align with your organization’s goals,” she says.

Just because something is a good goal does not mean it’s the right partnership if it isn’t in perfect alignment.

“You can cheer on and provide support to other partnerships working on other goals,” McCracken says.

As more companies join forces to tackle big goals some overlap in goals between different partnerships may be created, but that isn’t necessarily a negative result.

“While we don’t want to continue to reinvent the wheel, sometimes a little bit of overlap is good. There are many ways to solve problems, so we should continue to tackle the issues that align with our goals, and then share our results so others can learn from them and possibly build upon them,” McCracken says.

Planning for Partnership

Whether the soul of farming lies in the seed, the soil, or the farmers themselves, bringing together the knowledge and expertise of various stakeholders will be key in making a true impact for plant health in 2020, and it’s not something that will just happen naturally. That means seeking out appropriate, aligned partners, and investing in those relationships. That means communicating well, and sharing experiences and expertise to build efficiency.

“If you look at the major seed companies in the world, we’re seeing less of them than we did in the past; and the costs of seed now with improved traits, compared to these underdeveloped countries where there are millions of people who are hungry,” Watne says. “We know that food cannot simply be an item in a free market system. There are too many things at stake and we need the additional thought processes to support sustainability.”

Farmers, seed producers, soil health scientists and more; all of these voices have to be heard when we’re talking about such important goals as ending hunger and poverty. There is no quick fix, no single answer.

“When we look at the Sustainable Development Goals, and No. 17 especially, all of the necessary components are there, from technology to trade, and finance, policy and institutional coherence,” Keller says. “These goals are only possible if the different stakeholders trust one another and work together.”