A corn gene identified from a 118-year-old experiment at the University of Illinois could boost yields of today’s elite hybrids with no added inputs. The gene, identified in a recent Plant Biotechnology Journal study, controls a critical piece of senescence, or seasonal die-back, in corn. When the gene is turned off, field-grown elite hybrids yielded 4.6 bushels more per acre on average than standard plants.

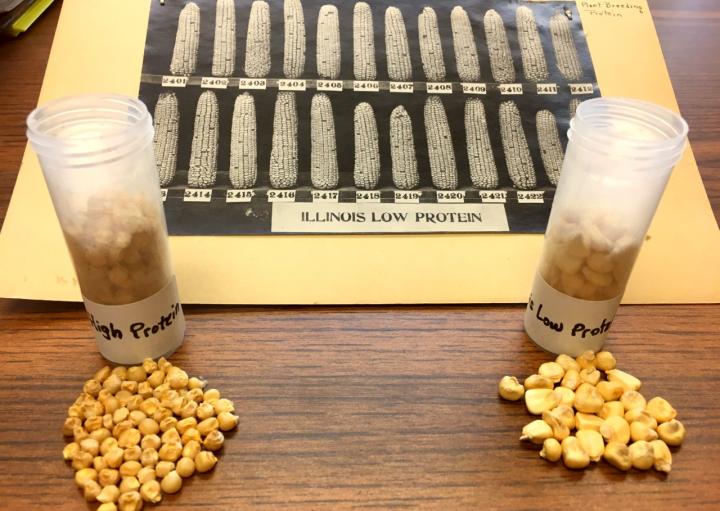

Dating back to 1896, the Illinois experiment was designed to test whether corn grain composition could be changed through artificial selection, a relatively new concept introduced by Charles Darwin just 37 years earlier. Repeated selection of high- and low-protein corn lines had the intended effect within about 10 generations. As selection for the traits continued, however, additional changes were noticeable.

“One of the things that was noted as early as the 1930s was that the low-protein line stays greener longer than the high-protein line. It’s really obvious,” says Stephen Moose, professor in the Department of Crop Sciences at Illinois and co-author of the study.

Staying green longer into the season can mean more yield. The plant continues photosynthesizing and putting energy toward developing grain. But, until now, no one knew the specific gene responsible for the stay-green trait in corn.

“The stay-green trait is like a ‘fountain of youth’ for plants because it prolongs photosynthesis and improves yield,” says Anne Sylvester, a program director at the National Science Foundation, which funded this research. “This is a great basic discovery with practical impact.”

The discovery of the gene was made possible through a decade-long public-private partnership between Illinois and Corteva Agriscience. Moose and Illinois collaborators initially gave Corteva scientists access to a population derived from the long-term corn protein experiment with differences in the stay-green trait. Corteva scientists mapped the stay-green trait to a particular gene, NAC7, and developed corn plants with low expression for the trait. Like the low-protein parent, these plants stayed green longer. They tested these plants in greenhouses and fields across the country over two field seasons.

Not only did corn grow just fine without NAC7, yield increased by almost 5 bushels per acre compared to conventional hybrids. Notably, the field results came without added nitrogen fertilizer beyond what farmers typically use.

“Collaborating with the University of Illinois gives us the opportunity to apply leading-edge technology to one of the longest running studies in plant genetics,” says Jun Zhang, research scientist at Corteva Agriscience and co-author of the study. “The insights we derive from this relationship can result in more bushels without an increase in input costs, potentially increasing both profitability and productivity for farmers.”

Moose’s team then sequenced the NAC7 gene in the high- and low-protein corn lines and were able to figure out just how the gene facilitates senescence and why it stopped working in the low-protein corn.

“We could see exactly what the mutation was. It seems to have happened sometime in the last 100 years of this experiment, and fortunately has been preserved so that we can benefit from it now,” Moose says.

He can’t say for sure when the mutation occurred, because in the 1920s crop sciences faculty threw out the original seed from 1896.

“They had no way of knowing then that we could one day identify genes controlling these unique traits. But we have looked in other corn and we don’t find this mutation,” Moose says.

Future potential for this innovation could include commercialized seed with no or reduced expression of NAC7, giving farmers the option for more yield without additional fertilizer inputs.

Moose emphasizes the advancement couldn’t have happened without both partners coming to the table.

“There’s value to the seed industry and society in doing these long-term experiments. People ask me why university scientists bother doing corn research when companies are doing it,” he says. “Well, yeah they are, and they can do things on a larger and faster scale, but they don’t often invest in studies where the payoffs may take decades.”

Source: University of Illinois