A closer look at the drivers behind and impact of the three mega-deals

Dow Chemical and DuPont are proposing to merge in a 130 billion USD deal; ChemChina is planning a 44 billion USD takeover of Syngenta and Bayer is pursuing a 66 billion USD takeover of Monsanto. It will not have escaped many who are working in or with the agribusiness: these are the three megadeals which have the potential to shake up the world of agriculture as we know it. To find out more about the reasons behind these deals we asked Garrett Stoerger, partner at Verdant Partners LLC to shed some light on them.

European Seed (ES): What were the main reasons for the six companies to engage in this merger & acquisition process?

Garrett Stoerger (GS): It’s important to set the groundwork first and we need to look at what are the drivers behind these deals. I think there are misconceptions within the industry about what’s happening here and in my view, there are several key drivers.

None of the six companies are doing this as part of a strategy that was in place even three years ago. Times have changed, and a lot of that is being driven by the relatively weak commodity prices that we’re seeing, relative to what we have experienced beginning eight years ago. Farmers have less money to spend on crop inputs, and they revert to lower cost options. The seed companies, for most of the last decade, have had great successes on the farm, selling new varieties, new seed treatments, and steadily increasing the price of those goods. It’s like buying a car. When people have money, they are more likely to opt for navigation or leather seating. Times were very good. Money at the farm gate was quite high, and farmers were putting large amounts of investments into their farming operations when compared to more difficult times in the industry. As that scale back started, earnings per share and other financial indicators that shareholders and investors look to, started to weaken. And all of a sudden there was a tremendous amount of pressure on these companies to produce more and better results in a struggling market. And if you can’t drive growth on the top line, you have to find ways to save money.

If any of these companies pull back on R&D spending, they consequently reduce their product pipeline, which is a short-term fix for a long-term problem. They can’t really afford to shut off the pipeline as a cost-savings measure. And so in this case they have looked to merge entities. As you can imagine, there is more cost efficiency in not having as many breeding locations across the globe, but scaling that down does not come without consequences.

Another driver, and this is a little bit of a consumer/political driver, there has been a fairly substantial reduction in the adoption of technology. At one time, and this is a very US centric opinion, farmers were asking for every possible trait that could be put into seed that is beneficial to them at the farm level. In the meantime, consumers have spoken and Europe has largely maintained its strong resistance against GM technology. And even in the US, there is now more awareness then there once was. People are more uncertain of science and technology, mostly because they don’t understand it. And as far as they are concerned, they would rather not have GM crops in their food, as they perceive current traits as not bringing them any direct benefits. Meanwhile, they don’t understand that the indirect benefic of GM is a cost savings in the grocery store.

The period from 2006 till 2014 were good times for the agricultural industry, possibly the best times we’ve ever experienced in modern agriculture in terms of cash flow at the farm level. It doesn’t take a crystal ball to predict that eventually something had to give. That is again a consequence of the tremendous commodity price support, and part of that was demand driven and part of that was supply driven. On the supply side there were two straight droughts in the Australian wheat market in 2005 and 2006, and that shortened that crop’s supply, so the price of wheat skyrocketed in the early 2006 timeline. Meanwhile, oil prices moved from 75USD per barrel to 100-120 USD per barrel, which in the US opened up the boon for corn ethanol. All of a sudden there is a new market leader in terms of corn usage – with 40% of US corn going to biofuel. Thirdly, commodity prices were further amplified by the fact that the USD weakened as foreign currency, so exports were more attractive. And the commodity markets had even more support and more fuel. And lastly, a further driver of this run up of commodity prices was the relatively unstable equity markets. Hedge funds and very large index funds saw more possibility, more upside potential in commodities than stocks and they started investing in a way like the grain market had never before seen. All these factors coupled, drove the agricultural markets to levels it had never seen before.

ES: What is going to be the impact on the seed industry outside of the six involved companies?

GS: The agricultural industry is largely made up of collaborations, cross licensing. Technology is being licensed between competitors, from large companies to small companies and vice versa. There is very much an interwoven web of licensing structures that are taking place all across the seed industry. In my view, as long as these stay intact, there is plenty of room for competition. It is only when those relationships start to crumble, that we may start seeing some blockages and barriers to entry. If you stop the cross licensing it becomes much more quickly an industry dominated by only a few players.

Generally speaking there are basically three types of companies:

Companies that are pure breeding companies, which don’t engage in any sales or marketing. They are in the business of developing new germplasm and technology.

Companies that in-license or buy the technology, and then develop it further and take it to the market. They are often not the developers of new technology, as much as people believe they are. Typically they license the technology from universities or they acquire it and then take it to the commercial level.

The third type of companies are licensees and marketers. They are specialists in relationships and have a strong customer base. They know what the farmers and customers in a certain region want, but have no intellectual property. To them, their value in the market place is to put the right seed product on the right acre.

Technically, a fourth type of company would be one that does all three of these functions, which historically has been who we refer to as the Big 6.

So the interwoven nature of the seed sector is also a factor that should be taken into account by anti-trust regulators when considering these deals. And in fact the anti-trust authorities have had in depth talks with several experts from the seed industry to get a better grip on where the overlaps lie.

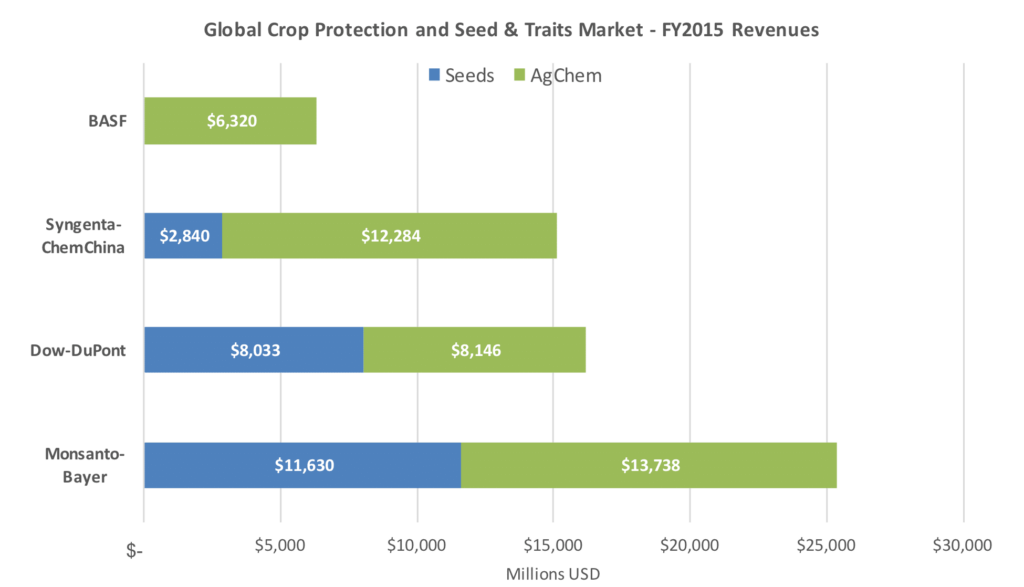

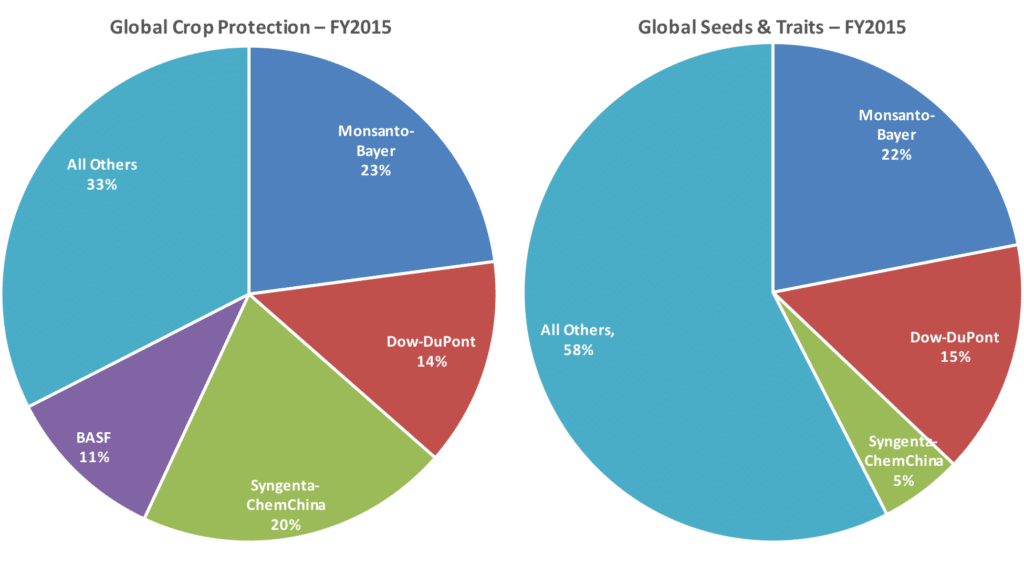

Source: Verdant Partners

ES: What do these deals mean for the farmers, in terms of choice and price?

GS: A lot of farmers reason in terms of fewer companies means less competition and this leads to fewer products and higher prices. Admittedly, it’s hard to see how any of these deals will lead to increased competition, but that is not to say that there will be a decrease of competition. Increased competition is not a driver for these deals. Instead, the drivers are cost efficiencies and returns to shareholders. I don’t think competition will suffer in the short term. And the regulatory bodies around the globe are making sure that appropriate divestitures do take place, so that any areas where there is tremendous overlap in the assets will be removed, in part or whole, and sold into the market.

That is probably the one aspect of these transactions that could lead to an increase in competition.

Right now so many of the significant agricultural holdings in the world are tied up in the big six companies. When you bring a few of them together, you force them to sell off select assets that are really the crown jewels of their business, and that could actually be a benefit for other companies.

We have seen a bit of this process in the past decade where after the acquisition of Seminis by Monsanto, the vegetable product portfolio was slimmed down from 62 to 25 crops and the germplasm of the discontinued vegetable species was auctioned off to other small and medium sized breeding companies, providing them with a very welcome injection of high value genetics.

As it relates to the higher prices, it was not two people in two companies who decided that the big six is the wrong number and should become the big four. There are forces behind the scenes that are way more powerful than any one person’s desire to merge or acquire, and a lot of that has to do with shareholder demands, while not fully understanding that agriculture has cycles. For people in the industry, we understand that this is a period where we’re going to experience less profitable times and we need to weather the storm and get through this.

In terms of choices and how that relates to the farmer, I think that anything that is demanded in the market today, will continue to stay on the market. Maybe the only difference is that there will be a different name on the bag.

The companies that comprise the big six have brought technology to the market and we give them a lot of credit, but the reality is that innovation has been done on a small scale by startups, by universities, and these organizations are not going anywhere. They are not part of this merger and acquisition process.

The very nature of the word innovation means that the products that are currently in the market will eventually be replaced by new products. Thus, I think there is going to be no lack of choices.

In respect to price, the biggest hindrance for increasing prices is the farmers’ profitability. I don’t think there is a lot of room to raise prices on the farm, because farmers simply cannot afford an increase in price. So all in all, the farmers, growers and producers of this world are fairly well insulated from these deals. I understand that there is concern, but I don’t think there needs to be a level concern from the reasoning of: fewer players means less varieties, means higher prices.

ES: Can such mega-deals make a bigger impact in tackling world hunger? And if yes, how?

GS: I don’t believe that the rationale for these transactions occurring has anything to do with these companies having suddenly decided to fight world hunger. These companies are doing that already, independent of one another, and will continue to do that after the process.

But it should be noted that feeding more people is part of the core mission of all companies active in agriculture. If your mindset is not to produce more food, then you’re probably in the wrong industry. The regions with the largest population increases in the next 30 years, including Northern Africa, India, parts of Asia, are going to place stresses on the global demand for food production in ways that we’ve never seen before. There are regions in this world that are so far behind agronomically and a tremendous amount of work can be done in those regions. From a company’s perspective, you can look at this from two sides. There’s the capitalistic side on how to make money on this opportunity, and there is also the philanthropic side of doing the greater good. And I think there is room to do the greater good, and still create some profit or at least break even.

Of course it is also true that the process should result in stronger and more robust companies and as such these companies can spend more of their resources on innovation, creating better varieties that are more suited for local conditions. The companies resulting from these transactions however, will first need to consolidate and repair themselves, before they are poised for continued growth and prosperity.

ES: What are the benefits for Monsanto and Bayer?

GS: The end result of the transaction for these two companies will solidify them as the global leader in seeds and crop protection. Monsanto is currently the global leader in seed, and with Dow and DuPont coming together, that leadership position was going to be challenged. So the transaction with Bayer solidifies them in a leading position.

At one time Monsanto was chasing down Syngenta, to bolster their position in seeds with crop protection. That didn’t happen, and several other events unfolded, where the company changed in a way from predator to prey. The Monsanto strategy, back then was to buy the entire business of Syngenta, and sell the entire seeds section. They were only interested in the crop protection side of Syngenta.

Both Bayer and Monsanto have vegetable and field crops, and it is almost a certainty that parts of both companies will need to be divested. For example, in North America, there is a decent amount of overlap in canola and cotton. And besides seeds, there’s the technology/trait side of things. Bayer owns the LibertyLink trait technology, and how does that survive in a mix with Monsanto that owns the RoundUp technology? So this transaction will create a considerable concentration of technology. Having said that, LibertyLink is a relatively small compared to RoundUp Ready in soybean and corn. However, this picture is a bit different in the canola market, where the share of LibertyLink is greater than RoundUp.

It remains to be seen how Nunhems, Seminis and other vegetable parts in this transaction will come out. The initial indications are that there is a good degree of complementarity, meaning that in certain crops or crop types one company is strong whereas the other company is weak, and in other crops and types it is vice versa.

The vegetable seed market is quite different from field crops, where in one vegetable crop you can have different types, maturities, sizes, regional adaptations and other specialties. And one needs to really look into this in a detailed manner to see if something really is an overlap. Antitrust authorities have sat down with seed industry experts to analyze these specificities into detail.

Bayer and Monsanto seem to be approaching the transaction in a conservative way, and they are proactively and pre-emptively offering concessions to the regulators, by putting forth certain assets, and in some cases even their crown jewels. For example, in North America, Bayer’s canola program is a fantastic program which would be highly desirable in the market place. So for Bayer to part with this program, is a huge concession, but obviously one they are willing to make to ensure this deals goes forward. There is so much more at stake than just the Canadian canola market.

ES: What are the benefits for Syngenta and ChemChina?

GS: With this transaction, ChemChina is going to have access to seeds and traits and specialized crop protection products like they have never had before. National food security has to be high on their hit list of what they are chasing, so this is a very strategic acquisition for ChemChina.

And for Syngenta the big benefit is that they won’t be acquired and parceled off, or harvested for the various components. The management teams, systems, and distribution networks, and so on stay in place and are not interrupted as is the case in the other two transactions. This deal with ChemChina will allow for more continuity with Syngenta, so they can hit the ground running. It will take some pressure off Syngenta to hit sales targets, and it will allow them to regroup and to strategically place themselves in the market. Besides, there is value in not making all the public disclosures that public companies must make, as you can keep thing a little tighter to the chest.

Another benefit is the likely facilitated access to the Chinese market to capitalize on the huge and growing Chinese population. It is very hard to get any good insights into the Chinese market, so there is no saying whether this will now open up China market for more biotech crops.

ES: What are the benefits for DuPont & Dow?

Once the merger is complete, sometime in late 2018, the merged entity will be broken into three new and separate entities, of which one will be a full agriculture focused company with the ag-related assets from both Dow and DuPont. Both Pioneer and Dow AgroSciences had parent companies to answer to, so this merger might be able to free up some of the agricultural potential in the new entity in the sense that it can probably be more nimble, and quicker to respond to changing markets. They won’t be as layered in with performance products, specialty chemicals, etc. as they previously have. The combined ag-entity will be a formidable opponent to some of the other giants.

ES: What perspectives do we have from other sectors than the seed industry? Such as the food and drink or the processing sector?

GS: For the food and drink sector but also for the milling and processing sectors, much is driven by consistency of their products, and this all starts with the seed. These other sectors might have reservations about these transactions if it would result in a decrease of product offerings. This consistency is important for any end-user of commodities. Some other products, such as high fructose corn syrup or sweeteners, are more commodity driven. But overall, consistency is of paramount importance. And if there is a strong enough demand, it is hard to imagine why any of those companies want to walk away from a relationship.

ES: Europe (the biggest anti-GMO region) is home to Bayer, which now owns the creator of the technology. What kind of an impact will this have on the acceptance of biotech in Europe and could these deals change Europe’s outlook on GM technology?

GS: For more acceptance of biotech varieties and food in Europe, the sheer fact that Bayer is buying Monsanto is not enough. Europeans won’t have a changed opinion now that the biotech varieties are coming from a European company. It is has much more to do with consumer preferences – consumers have been asking themselves “why would we want any biotech in our food?” Historically, biotech traits have been for the benefit of farmers, with the purpose to combat pests and weeds. And consumers in the US have been largely accepting these traits, whereas in Europe the consumers have been largely opposed to such traits.

Whereas we have been debating whether these traits are safe, what really has to change is for consumers to know whether these traits make their lives better. A consumer wants to see benefits for them in the way of improved shelf life, added nutrition, and so forth. With some of the new breeding methods, this whole debate will change. These new technologies will be able to speed up regional adaptation of varieties, which is going to be especially important for those regions which can’t feed its inhabitants. Other examples are crops that can be grown in more extreme weather conditions, including drought and salinity tolerance, or that can be grown in a more sustainable manner. All of these examples, combined with increased yield, will provide enormous benefits to mankind and should be part of the discussion as we go forward. We need to better explain to the consumer what changes have been made, and especially what the benefits of such crops are, such as the ability to feed more people. As we go forward with the debate, I am expecting less opposition by consumers to such crops if they are aware it is truly beneficial to the global food supply.

With this next generation of breeding methods we will be able to make selections that provide clear benefits for the consumers and then we’ll see Europe come around. These new methods have the potential to be the most significant discovery of the last century for agriculture, comparable to the discovery of hybrids. There is now a multitude of small and large companies and public institutions that are now using these new methods and they are making remarkable advancements. It would be a tremendous pity if such methods would be regulated and removed from the toolbox of many small and medium sized companies and public research institutions. In this respect, we can’t stand in the way of ourselves. It is selfish of certain special interest groups to oppose such methods when you have a billion people going to bed hungry.

Garrett Stoerger is Partner at Verdant Partners LLC

Verdant Partners LLC is recognized as the leading business brokerage and consulting group for agribusiness. Founded in 1998, Verdant’s focus covers the span of crop production agriculture, with transaction experience extending beyond seeds and traits to all facets of crop-based agribusiness. Since 1998, Verdant has initiated and managed successful transactions and alliances valued at more than U.S. $2.2 billion. We advise privately held businesses, public corporations, multinationals, venture and buyout funds, and technology companies throughout the world.

Where on the web: http://www.verdantpartners.com/