Great taste is back on the agenda for fruit and vegetable breeders.

What do people like about tomatoes? The answer probably isn’t “disease resistance” or “shelf stability.”

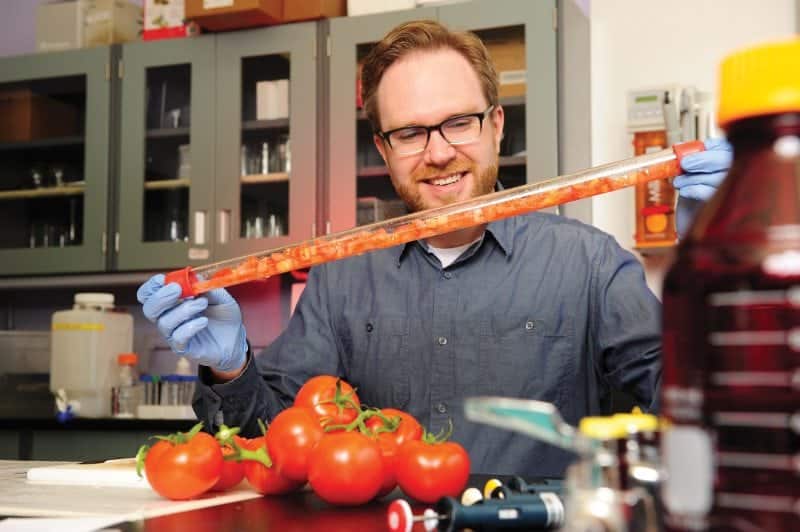

People like tomatoes for their flavour and texture, says David Liscombe, a research scientist and biochemist at Vineland Research and Innovation Centre, a not-for-profit research institute that promotes the horticulture industry in Ontario, Canada. But for too long, taste and other so-called “consumer traits” have been sidelined in favour of production traits when it comes to fruit and vegetable breeding.

Consumers have become used to underwhelming supermarket offerings — over-refrigerated, tasteless fruits and vegetables, sometimes accompanied by a mealy texture.

Liscombe aims to change that.

“Market data shows that consumers are willing to pay more for products that resonate with their values, and products they deem have superior flavour,” he says.

He’s the lead on a seven-year project funded in part by the Ontario Greenhouse Vegetable Growers that aims to release a superior-tasting tomato-on-the-vine (TOV) hybrid by 2020. Six Vineland research groups — in breeding, pathology, applied genomics, biochemistry, consumer insights and business development—are all focused on the project.

“It’s about understanding from the get-go what consumers like and dislike about tomatoes, and applying all the latest technologies to get us to a tastier tomato, which includes understanding its chemistry and genetics,” says Liscombe.

These are ideas that have made progress in the industry during the past decade or so, thanks to the hard work of tomato research groups such as that of Liscombe’s collaborator, Harry Klee of the University of Florida. Klee has been focused on flavour since the 80s.

But flavour is a tough nut to crack. Despite advances in equipment and DNA sequencing technology, which help breeders zoom in on the genetics behind great-tasting tomatoes, taste is complex. Tomato aroma is influenced by sugars, acids and volatile chemicals, which — present in different ratios in different varieties — can have dramatically different impacts on the palate.

The tomato fruit, explains Liscombe, makes about 400 different volatile chemicals—those that you can smell. Only about 10 per cent of these, or about 40, are involved in flavour production. Some of these chemicals are associated with consumers liking a tomato when they are present in the fruit at higher levels, but tomatoes can also produce volatiles that make them less appealing.

The same principle goes for texture, which Liscombe says consumers find at least, or more important, as flavour in tomatoes.

In the past, breeders were limited to working on just a few traits at a time, due to the fruit’s complexity.

“Now we have all these different high-tech tools that allow us to track many traits at the same time,” he says. “There’s no question that the more traits you’re interested in, it does get more challenging. But we think we can do it.”

Liscombe’s team’s results will benefit the industry as a whole: his team has a smaller project, nested under a larger Genome Canada effort, that aims to produce breeding lines with differentiated aromas that will be made available to other seed companies and breeding programs.

“We’ve had a lot of positive feedback about the work that we’re doing here, and we hope that other programs will shift their priorities and think some more about consumers from the beginning, rather than developing a product and asking consumers at the last minute if they like it,” he says.

A Memorable Eating Experience

This newfound focus on flavour is not confined to tomatoes. In the apple breeding industry, it’s actually been on the agenda for decades.

There’s less fruit to show for it only because of the length of time it takes to develop and release new apple varieties and grow trees — sometimes up to 30 years from start to finish.

David Bedford has been an apple breeder at the University of Minnesota for 38 years. He says breeders have been trying to develop tastier apples since the 1960s.

“In my mind, if we’re not producing something with a memorable eating experience, we’re just wasting our time,” he says. “We have plenty of apples that look nice enough on the shelf and are durable, but when you get home and the lights are out you still have to eat it.”

Bedford is the brain behind the popular Honeycrisp apple, which reset the industry standard when it was released in 1991. More recently, Bedford has released SnowSweet, Zestar and SweeTango — the latter was released in 2009 and has quickly gained popularity across the U.S. and eastern Canada. In 2017, Bedford will release the Rave/First Kiss apple, a grandchild of Honeycrisp.

In order for a new apple variety to make it all the way to market release, it has to be extraordinary, says Bedford.

“In our program, we have put the most emphasis on the two traits that I think affect this memorable eating experience — that’s texture and flavour. If we don’t achieve one or both of those, we don’t release a variety.”

Bedford’s favorite example of an apple that doesn’t meet par is Red Delicious. When he started his job nearly 40 years ago, few apples rose above its quality in terms of texture: apples then were generally divided into two categories then, “soft/mealy” and “hard.” Of the two texture attributes, the latter was preferable, but with Honeycrisp a third category was added: crisp. All of the apples since have been bred to Honeycrisp’s new standard.

When it comes to flavor, Honeycrisp raised the bar again with its complex sweetness. In new apples, Bedford looks for high levels of sugar and acid—an apple that has both will be pleasantly complex. He also looks at aromatics, the presence of volatile chemicals that actually change the way an apple tastes.

Even with the most advanced conventional breeding techniques at his disposal, Bedford says it’s still extremely difficult to breed an apple with desirable eating qualities and production characteristics. His program looks for about 20 characteristics in every apple, ranging from aroma to tree form to winter hardiness. Any apple released must rate high on all 20 scores.

Of the original crosses Bedford and his colleagues developed in the lab, only one in 10,000 typically makes it to supermarket shelves.

“Putting the genes of two parents together, everything changes — you don’t get to say, ‘I’ll keep 19 characteristics and change just one characteristic.’ It’s like a Rubik’s cube; every time you flip one characteristic, the others change too,” he says.

DNA sequencing means breeders can line up an apple’s background genetics prior to making crosses, but they still don’t know how those genes will be expressed until they see and feel the fruit.

“Now what that means is we make smarter crosses, and in theory, we’ll have a better percentage. Instead of one in 10,000, maybe we’ll have one in 5,000,” says Bedford. “But the bar is constantly being raised in terms of what a good apple is. Apples I throw away now would have had potential to be released 15 to 20 years ago.”

Bedford is encouraged by the new focus on flavour in the fruit industry; it signals a sea change in the qualities consumers value.

“When Honeycrisp was introduced, no one thought they’d pay 30 per cent or more for it, but the price has held and the volume has gone up,” he says. “That’s really very encouraging for me as an apple breeder — the public recognizes different levels of quality.”

Consumer Trends

Consumer trends are at the heart of the shift in breeding priorities across the horticulture industry.

Stakeholders are beginning to recognize consumer willingness, in certain demographic categories, to pay more for better products, says Carol Raithatha, a fellow at the Institute of Food Science and Technology in England and consultant in sensory evaluation.

She’s worked on projects involving a variety of fruits and vegetables, including apples, avocados and potatoes, using panels to compare sensory profiles of different cultivars or varieties and conducting research to understand consumer preferences.

“In general there is more segmentation in the market, probably as a result of retailer efforts to offer greater choice and add value through differentiation,” she says. “So the range of qualities and varieties of various fruits and vegetables available with unique sensory properties has increased.”

One example Raithatha notes are small, sweet apples targeted at children.

Raithatha says many consumers still prioritize cost over sensory qualities, but a growing segment of consumers, such as millennials, are willing to spend more money on better-tasting fruits and vegetables. “In some cases this is associated in their minds with other characteristics, such as organic, ethical or healthy,” she says.

She points to a project in New Zealand focused on developing a red-skinned, red-fleshed apple, which she says seeks to up the ante of a traditional offering by increasing its sensory appeal.

“In general, the appeal of the product may be much more if there is a specific sensory characteristic that consumers find novel and appealing, and that can be linked with unique nutritional or other health benefits,” she says.

But even if consumer trends can be generally identified, individual preferences are complex and hard to pin down. Although cultural approaches to particular fruits and vegetables can dictate general trends, variations in preference can be “very large” even within regions, influenced by psychology, physiology, context and societal influence, says Raithatha.

In the end, who really knows why consumers reach for one apple instead of another?

Bedford says in the apple industry, breeders can’t focus too closely on consumer trends. “It’s hard to know what consumers will want in 20 years. But most consumers don’t know what they want anyway,” he says.

When he started breeding apples 38 years ago, he asked apple growers what they wanted to see in new apple varieties. They asked for “redder” versions of apples they were already growing.

“Growers and consumers don’t know what the possibilities are. It’s up to us to generate those possibilities and see what they do like,” he says.