A new variety of grass goes through a lengthy process lasting up to 15 years before being granted official approval. At the start of the breeding cycle, the breeding objectives for the new variety are defined. Here, product managers and breeders must have a talent for recognising future trends if they are to remain competitive. However, the aim of breeding is not necessarily to respond to new trends, but to continuously optimise existing breeding traits, such as wear resistance, sward density and winter hardiness, in order to create the ideal turf variety. DSV breeds perennial ryegrass for turf at its Hof Steimke breeding station in Asendorf, Germany, by selection and hybridisation. To begin with, around 30,000 individual plants of different species and types are planted in individual trays. These are selected for specific traits, such as sward density, fineness of leaf, colour, tolerance of cutting, disease resistance, vitality and shoot density. Using modern breeding techniques, positive plants are selected—high-quality plants with an optimal combination of desired traits.

The next step is to carefully observe these elite plants, and describe their appearance in minute detail, which is essential for accurately combining matching plants to produce homogenous new varietal candidates.

This produces new source material for ‘polycrosses’, each consisting of four to 20 elite plants. These are planted in insulated cubicles to protect them from foreign pollen. More than 200 polycrosses of perennial ryegrass alone are produced each year.

After an interim propagation process, these candidates undergo more than three years of testing in Asendorf to determine their suitability for turf. Approximately 4,000 plots are planted annually, and monitored for a three-year period. This generates a continuous flow of data from more than 12,000 turf plots.

“During this time the turf is subjected to continuous stress tests because only then do differences between individual breeding lines really become apparent,” says Cord Schumann, director of turf breeding. Amongst other things, tolerance of close mowing is tested by mowing the turf three to five times per week, down to cutting heights below 10 mm.

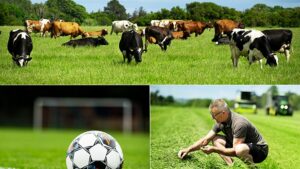

A studded turf roller is used to determine whether a turf strain is suitable for sports pitches. This simulates the load applied to the turf during a football match or training session. The studded roller is used four times per week to test maximum loading. In addition, the sports turf is mown several times a week to a height of 25 mm.

Schumann also has a special test in his repertoire. “I carry out a sensory test on each variety. This involves walking barefoot across the different plots of turf, and feeling the sward density. My eyes might tell me that I’m looking at a thick grass sward, but with this simple test I can pick up other nuances in sward quality and density’,” he says.

Apart from turf characteristics, another important factor in the production of seed is seed yield. Through breeding and the improvement of cultivation methods, the average seed yield for perennial ryegrass has increased by approximately 500 kilograms per hectare in the last 10 years. Tests are carried out to determine the seed yield potential of turfgrass strains. There is usually a negative correlation between seed yield and turf quality in individual varieties.

After this extensive test phase, the most suitable strains are selected for propagation in the nursery. It has taken 10 years to arrive at this point. Now the variety is registered with the Federal Plant Variety Office (Germany), or the relevant authority abroad.

After the application there is a further wait of at least three years while the respective institutions conduct official tests before approval for the variety can be granted.

Success in the turfgrass breeding programme has averaged around 30 per cent in the last 20 years. This can be explained by the fact that compared with cereals, for example, turf breeding is a comparatively young discipline. Individual sources place the start of turf breeding at around 1900, although references to structured breeding programmes actually appear only from the early 1960s. Compared to other crops, an average breeding progress of virtually 1.5 per cent over a 20-year period is an outstanding result. This assessment is based on the results of the top 10 varieties on the well-known Sports Turf Research Institute’s turfgrass seed trials list, Table S1 (perennial ryegrass for sports uses) published by the UK’s British Society of Plant Breeders.