A closer look at the voting behaviour of EU Member States.

Several authors suggest there is a gridlock of the European Union’s approval process for genetically engineered crops. To test this hypothesis, we analysed the voting behaviour of EU Member States for voting results on the approval of GE crops from 2003 to 2015. Unfortunately, no reliable data is available pre-2003—a time which includes the EU’s ‘quasi-moratorium’ on GE crops.

In terms of the approval process, it is the European Food Safety Authority that determines the safety of a GE crop. Once that is done, the Standing Committee on Food Chain and Animal Health (SCFCAH) votes on the application. If the SCFCAH does not reach a decision, the Appeal Committee (pre-Lisbon Treaty is known as the Council) votes on the application. If again a decision is not reached, the final decision is left to the European Commission (Figure 1). All EU Member States are represented on both committees; decisions are made by a qualified majority voting system, the rules of which have changed over time.

Voting Behaviour

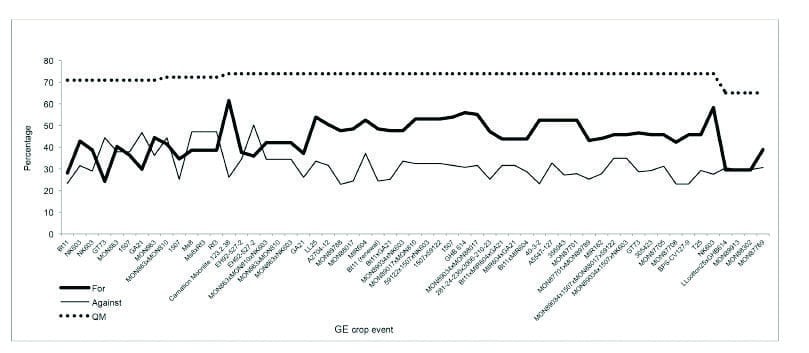

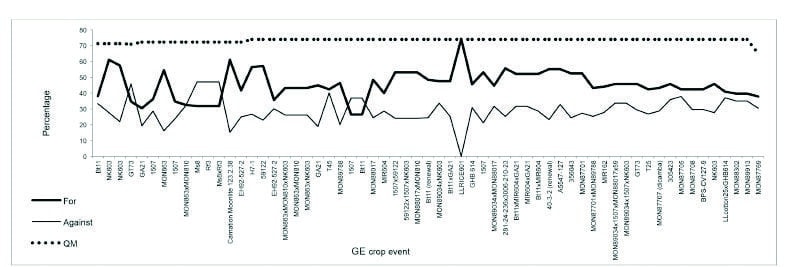

The analysed data includes 50 events as well as 61 ballots at the SCFCAH and 57 ballots at the Council/Appeal Committee. It should be noted that the EU’s membership has grown over time. Therefore, the number of voting opportunities per Member State is a function of how long it has been a member of the EU and the number of ballots during its membership.

Generally, the longer a MS has been a member, the higher the number of voting opportunities. The Netherlands, Sweden, Finland, the United Kingdom, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Romania, and Spain have voted ‘for’ with a frequency of at least 80 per cent. Austria, Luxembourg, Greece, Hungary, Cyprus, and Lithuania have voted ‘against’, with a frequency of at least 80 per cent, whereas Italy, France, Bulgaria, and Ireland abstained at least 40 per cent of the time at the SCFCAH. Finland and the Netherlands always voted ‘for’ and Austria always ‘against’ at both the SCFCAH and the Council/Appeal Committee. Croatia, Luxembourg, and Latvia have never voted ‘for’ at the Council/Appeal Committee.

The SCFCAH represents the first step in the political decision-making process. Should MSs fail to vote in favour of an application here, the political process continues with the Commission becoming involved (Figure 1). Descriptive statistics indicate the voting behaviour of the SCFCAH and the Council/Appeal Committee is similar (Figures 2 and 3).

We treated every ‘for’ vote as a positive statement for supporting a GE crop’s authorisation. The ‘against’ and ‘abstain’ votes, and several forms of absenteeism, were interpreted as negative statements opposing authorisation.

We used a set of logistic regressions for testing whether a MS’s identity, an applicant’s domicile, and a crop plant’s genetic trait are suitable explanatory variables for explaining a MS’s voting decision. This was done by first testing a MS’s identity, and then adding explanatory variables. The rationale for using this method is to assess whether voting decisions can be explained by factors associated with a MS’s characteristics (i.e. endogenous factors), or whether MS-specific effects prevail if explanatory variables based on qualitative information (e.g. crop type, or the crop’s intended use) are added to the model.

Theoretically, what appears to be a MS-specific effect may, in fact, reflect a MS-specific concern or opportunity leading, respectively, to a negative or positive vote. For example, Scandinavian MSs tend to accept (vote ‘for’) GE crops, but it is unknown whether these MSs’ voting behaviours are related to liberal and open-minded societies, or whether the positive votes are associated with, for example, factors favouring the MSs’ bio-economies (agricultural and biotech sectors). We use a set of logistic regression models for disentangling these factors, and for testing if they can be used for explaining the variation in voting behaviours.

The analysis shows that a MS’s identity (i.e. endogenous factors) is statistically the most significant factor driving voting behaviour. Other factors, such as a GE crop’s characteristics, play an unimportant role (i.e. do not influence the voting outcome—all GE crops are seen in the same light) in explaining MS voting behaviour in the context of our study and assumptions. This empirical finding supports the gridlock hypothesis. We have also found an overall positive time trend suggesting a persistent, but slightly weakening, gridlock. We postulate that it is unlikely in the foreseeable future for this trend to persist to the point where a qualified majority is reached.

Changing the Gridlock

We assume that each MS casts its ballot independently. The only positive contribution toward achieving a qualified majority is a ‘for’ vote. We therefore scrutinised each ballot for all MSs that prevented a qualified majority, namely those that voted ‘against’, abstained, or were absentees. From this subset of voters, we found the minimum number of MSs needed to achieve a qualified majority and who they were. In practise, we sequentially added MSs’ votes until a qualified majority could theoretically be achieved. When counting the number of MSs in this subset for ballots in which more than one MS of equal rank (vote weight) could have contributed to the total, we counted them all (consistent with our assumption of independence).

Three of the four ‘heavyweight’ MSs, namely, France, Germany, and Italy (the UK is the fourth) feature prominently in preventing a qualified majority. Since its accession to the EU in May 2004, Poland has become an important and consistent opponent (contributor to the ‘against’ vote) due to its sizeable vote weight, while Spain (Poland’s equal in vote weight) became a consistent supporter from 2007 onwards. Although the number of ballots with the latest double majority voting rule is low, early evidence reveals that the influence of Germany, France, and Italy—in this order—on achieving a qualified majority has strengthened, due to their new, larger vote weights.

Voting Results: No Change

The status quo of not reaching a qualified majority is likely to persist unless Germany, France, and Italy collectively change their positions to a ‘for’ vote supporting GE crops. The 2015 proposal by the European Commission for MSs to ‘opt out’ of approvals for cultivation is designed, in part, to ‘improve the process of authorisations’, according to the EC (i.e. facilitate an increase in the number of GE crops authorised for cultivation in the EU). According to our results, this outcome is unlikely, as it would require more MSs to vote in favour of approval. This would require at least two of the three heavyweights (France, Germany, or Italy) to change their latest voting behaviour. Importantly, it would require them to vote in favour of the most sensitive use category, namely cultivation.

The strong policy signals from Germany and France against cultivation of GE crops further supports our doubts that their voting behaviour will change in the foreseeable future. Italy might be the only heavyweight likely to change—this is based on its historical voting behaviour and demand by some of its pro-biotech farmers to access the technology. Even if the opt-out proposal does not result in a qualified majority for approval, the time the EC takes after the voting at the Appeal Committee could shorten, as the EC might be under less pressure from MSs to delay a final decision, and can therefore justify accepting the European Food Safety Authority’s favourable opinions by indicating MSs that had voted against cultivating GE crops in their countries had, in fact, opted out anyway.

Editor’s Note: This contribution is a summary of the paper ‘EU Member States’ Voting for Authorizing Genetically Engineered Crops: A Regulatory Gridlock’ in the German Journal of Agricultural Economics 64 (4): 244-262, by Richard Smart, Matthias Blum and Justus Wesseler.