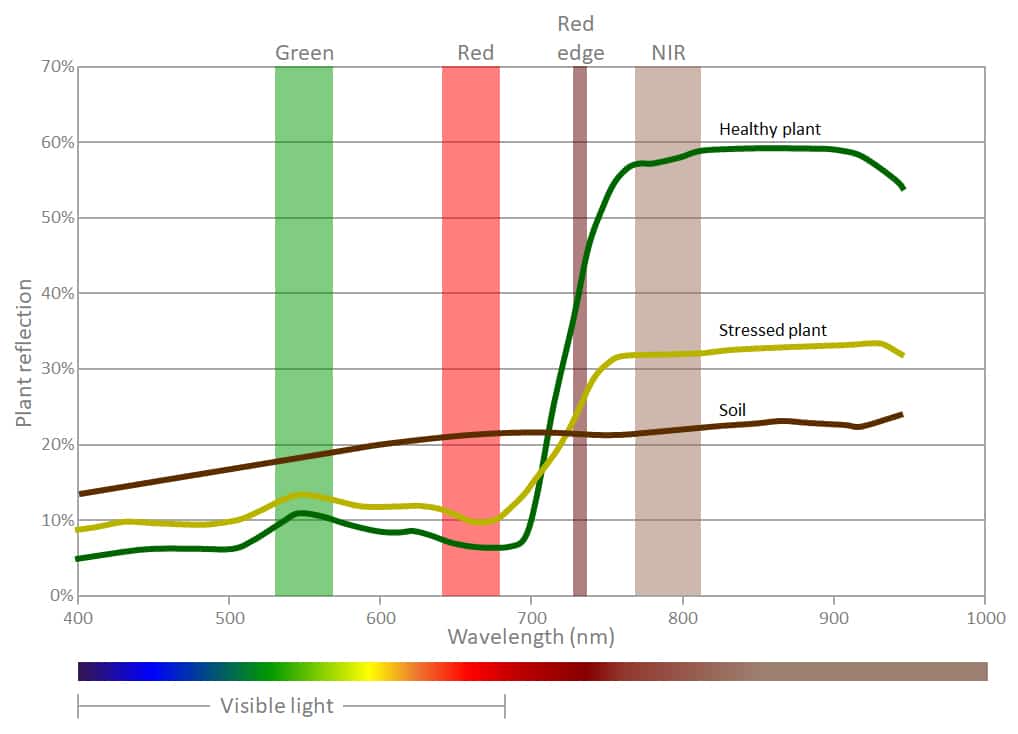

As I walk through our turf trials I sense a quiet humming sound not unlike that of a bumble bee, though it seems to be coming from somewhere far above. I look to the sky and there it is – a small four-propeller “Unmanned Aerial Vehicle” or UAV harboring a camera on a stabilizing gimbal and a peculiar little device that doesn’t seem to be standard carrier load. The little device is a multispectral camera which records images in four narrow light spectra; green (530-570 nm), red (640-680 nm, red edge (730-740 nm), and near infrared (770-810 nm). Each of these spectral images contains information about vegetative growth. Combined into a vegetation index, they can provide breeders with detailed information on traits such as crop cover, density, disease, and establishment.

These are traits that breeders normally score on a 1-9 scale by visual inspection, and statistical records prove they are really good at it both in terms of accuracy (evaluating correctly) and precision (small differences between repeats). They are also fast: A turf trial of several thousand plots is usually scored in less than few hours. So, one may validly ask: “Why using drone imaging that usually takes a lot of post-processing as a substitute for what is simple, intuitive, and documented to work well?” I would say there are two, perhaps three major reasons why DLF has decided to use drone imaging at least as part of forage- and turf evaluation:

- For certain traits, such as disease scoring, precision is higher. Firstly, the resolution in vegetation data from images is higher than 1-9. Secondly, image analysis is not biased, which may be the case for breeders after having scored some thousand plots – especially in situations where disease attacks are weak.

- Drones will allow to increase and repeat the number of scores, and the drone imaging enables breeders to file important observations at time points where they are busy with other tasks. Such information would otherwise have been lost or limited to one or two observations. Now the images can be analyzed during winter, when field work is typically reduced.

- Commercial platforms are already offering farm solutions, where customers upload drone images and gets agronomic data back. Once these platforms can handle massive plot numbers, drone-based scoring may even be faster than visual inspection. A 20.000 plots 1×1 m² trial field equals that the plant breeder has to do a half-marathon just to take just one score.

Will breeders become superfluous? Not likely. With his eye the breeder also carries that intelligence, which for example can perceive the difference between true winter damage and low coverage caused by bad establishment the previous year. In such case the breeder would assign the correct score and drone images not. So, next time I walk through our turf trials I expect to hear humming again mixed with whistling from a happy breeder who can have even more data and high precision with no extra work.