The market is growing for ornamentals that need fewer inputs.

Today’s gardeners want to do their part for the environment, seeking flowers and other ornamental plants that need less water and other inputs. And, as they do for all consumer trends, seed companies are meeting this market demand. While no one knows exactly how much climate change will further impact weather patterns, breeders are increasingly focusing on developing flowering plants that thrive in challenging environmental conditions, from prolonged dry periods and heat waves to sudden dips in temperature.

Consumers are very open to hardier old favorites, but they are also interested in anything new that’s water efficient and withstands the heat. It’s an extra bonus if these plants support bees, butterflies and other pollinators. Most ornamental plant breeding in the United States happens in the private sector, but one of the few public breeders, Mark Bridgen at Cornell University’s School of Integrative Plant Science (plant breeding and genetics) says he and his colleagues are having discussions about climate change and seed traits related to drought resistance.

Progress so Far

Syngenta, a leader in breeding hardier ornamentals, is fully recognizing the ‘climate smart’ gardening trend and changes in plant selection.

“As an example, community plantings of ornamentals in the upper Midwest and Europe were mainly regular bedding plants,” Syngenta’s global strategic portfolio manager, flowers Mike Murgiano says. “But now it’s becoming more a mix of subtropical crops, grasses and other resilient plants.”

He adds that consumers also like flowers in pots on their patios, and these plants suffer more from extreme heat and drought than in a yard setting.

Syngenta offers many varieties specially bred for heat and drought tolerance, including a group of species under a line called ‘Heat Lover.’ The company’s drought and disease-tolerant ‘Zydeco Fire’ Zinnia and ‘Dekko MAX Pink’ Petunia both captured 2025 All-America Selections Awards. Murgiano adds that one of their Impatiens series can stand the heat and sun much better than the traditional New Guinea impatiens that are currently on the market and still excel in the shade.

Roses are another ornamental flower group with water-efficient cultivars already available, with further improvements to come, including cultivars called Iceberg, Arctic Blue, Lemon Fizz and Hansa. The Seafoam is another to note. Not only is it water-efficient but it’s also what’s known as a ‘ground cover rose’ that helps maintain soil moisture levels after rain or watering.

Among the hardy daisies on the market today is the classic white-petalled Shasta, which sports the deepest of daisy root systems. It comes in varying heights, widths, bloom sizes and petal arrangements, for example the 8-10” White Lion from Ball Horticulture. The company’s Whitecap Shasta is frost tolerant as well.

Breeding for Success

In developing the new “cutting edge” ornamentals with heightened resilience to stress, both conventional and novel molecular techniques are being employed by breeders, as noted by a group of geneticists from several public institutions in India in their 2024 book ‘Molecular Breeding in Ornamental Crops: Current Trends and Future Prospects in the Genomic Era.’ This team explains that “as the floral industry dynamically responds to market demands, it unveils substantial potential for diversifying the spectrum of ornamental plants.” This is partly because ornamentals have an inherent heterozygosity that enables significant variation in first-generation crosses.

Among the approaches ornamental breeders are now using to develop heat/cold tolerance and other traits are mutation breeding (using both chemical and physical agents) and molecular approaches involving CRISPR-Cas9, TALENs and other gene editing tools. Marker-assisted selection, GWAS and QTL mapping and virus-induced gene silencing are also effective, report the Indian scientists, to enhance overall ornamental plant performance and enhance specific visible traits such as petal size.

Murgiano says Syngenta’s ornamental breeders are using multiple traditional and newer techniques ranging from induced mutations to molecular marker-assisted breeding, as much as ornamental sales can support (that is, the breeding budgets for field and horticulture crops are much larger).

“Breeding for ornamentals also has an added dimension in that when we present a new product, we need to present a line of colors in order to make it relevant,” Murgiano explains. “It’s like a TV show. You can’t just produce one episode but need a whole season.”

Syngenta senior breeder Todd Perkins and his colleagues are carrying out testing of new hardy ornamental selections at multiple locations with high temperatures both day and night, low relative humidity and high solar radiation. Murgiano says selecting under extreme conditions and making directed crosses with these selections produces the best-performing plants, but the breeding team also works on specific aspects related to tolerance to extreme conditions such as root development.

“An interesting trial we did a few years ago was on evaporation of several of our crops,” he says. “Within a crop, we did find significant differences between selections and varieties. But our main insight was that there are certain crops, like pelargonium, that have overall much lower evaporation rates (a much better water efficiency) than even the most efficient petunias. Combining these insights with the actual tests under extreme conditions result in higher-tolerant plants to serve market needs for the future.”

Native Plants

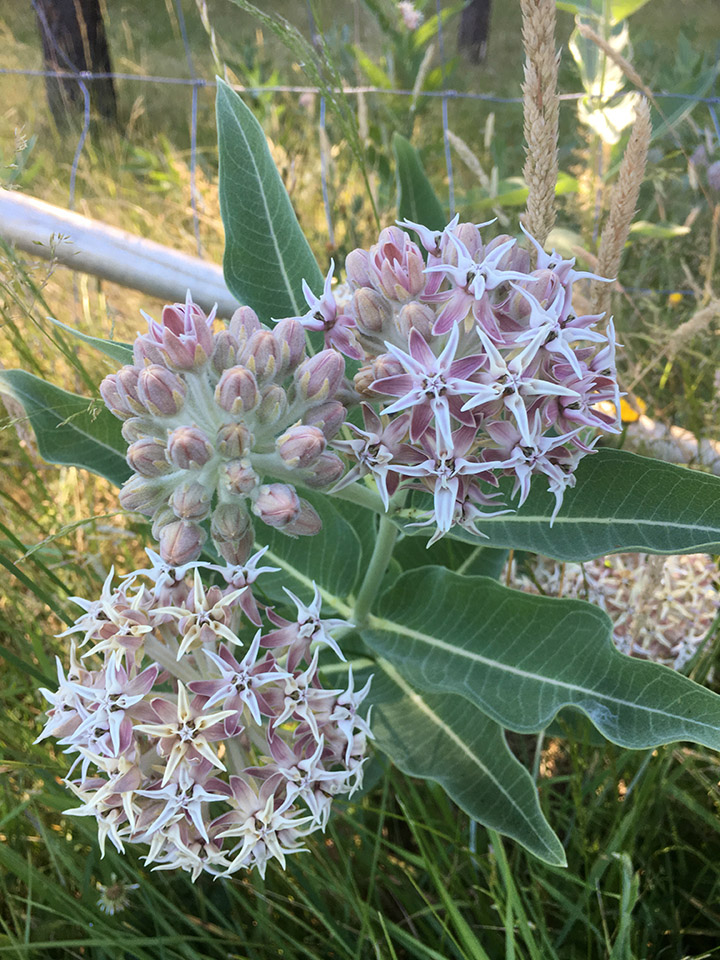

In any discussion of climate-friendly plants, native plants – Mediterranean species like lavender and sage, but also succulents and many others indigenous to North America – cannot be ignored. Indeed, they’ve seen a surge of popularity in recent years from homeowners who want to use less water and fertilizer, while also supporting local pollinators.

Prairie Moon Nursery in Winona, Minnesota, offers the largest 100%-native species collection for retail sale in the United States. The company sells seed in packages ranging up to a pound in weight, and also sells some potted plants.

“Many homeowners have dry soil, or a sunny, hot part of their yard where not much will grow,” Prairie Moon Nursery director of marketing, sales and service Becky Klukas-Brewer says. “More consumers are looking at native plants for these conditions. They are extremely versatile and able to survive in harsh conditions. We do not breed them to be hardier as they are naturally hardy. If you allow native plants to reproduce under natural conditions, the hardiest survive and they adapt over time to their changing environment.”

Prairie Moon offers over 700 species right now, but Klukas-Brewer says there are a lot more species that they could add, even just from within Minnesota.

“It’s a slow process to harvest seed, determine germination methods, grow it out, but we continue to add species,” she notes. “We could add hundreds more native species.”

Siskiyou Seeds in Williams, Oregon, offers a few native plants, but most of its 225 flower varieties are commercial cultivars that are hardy and locally adapted to the Pacific Northwest. This farm-based seed company develops and distributes only open-pollinated organic seeds, a premium product business model which helps support R&D for adding more native varieties in future.

Founder and director of operations Don Tipping was recently in Africa, for example, and is trialling millet and sorghums from there to see if they do well in his region.

“These plants make nice ‘fillers’ in flower gardens and spark conversations,” Tipping explains. “Whatever crops farmers grow in a place like Africa have to survive. They don’t have the money for crop inputs, and they don’t have irrigation for the most part. People here are taking notice of these things, that native plants are very hardy and resilient.”

Reflecting on the growing popularity of both hardier native species and commercial cultivars, Tipping highlights the last 100 years of breeding.

“The commercial prima donnas, you could call them, with their beautiful large, long-lasting blooms in vibrant colors are native plants that have been bred for these traits over a long period,” he notes. “It’s incredible what we have been able to accomplish with classical breeding alone. Dahlias, for example, were a food crop in Mexico grown for their tubers, and there are now 58,000 cultivars. But with the focus on the prima donna traits, resilience traits have been overshadowed to some extent. And now we see a re-introduction of drought tolerance back into the commercial cultivars, putting back some of what their ancestors had.”

And while he’s pleased that with all commercial crops in the western world — from ornamentals to horticulture to field crops — are gaining genetics that allow them to adapt to periods of drought and erratic weather that can come from climate change, Tipping mentions another piece to the puzzle.

“Regenerative agriculture, which is the other answer to climate change, is now being talked about in mainstream media, so that’s another big change,” he says. “I never thought I’d see that in my lifetime. So, while it’s good to see hardier ornamental varieties becoming available, hopefully all home gardeners, and farmers as well, will also learn about regenerative practices and use them.”