Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) and its historical role in delivering field-ready cultivars is evolving — a transition that has ignited conversation about the need for a solid strategy to ensure the long-term health of plant breeding in Canada.

That was the major takeaway from a panel discussion held at the Interprovincial Seed Grower Meeting in Calgary, Alta. on Nov. 26. The meeting was hosted this year by the Alberta-British Columbia Seed Growers (ABCSG). The panel, facilitated by Seed World Canada editor Marc Zienkiewicz, featured six experts from various areas of the plant breeding sector:

- François Eudes, who holds dual roles at AAFC as research, development, and technology director and national science lead for breeding innovation and crop germplasm development

- Holly Mayer, director of science partnerships at AAFC

- Rickey Yada, dean of agricultural, life, and environmental sciences at the University of Alberta

- Curtis Pozniak, director of the Crop Development Centre at the University of Saskatchewan

- Jodi Souter, Nuffield scholar and founder of J4 Agri-Science

- Robert Graf, retired AAFC winter wheat breeder and science advisor for SeedNet

Evolving Roles in Plant Breeding

Eudes started off by emphasizing that AAFC’s role in plant breeding is evolving.

“We’ve been in this business for more than 100 years,” Eudes explained. “But the way we conduct science has to adapt to challenges farmers face, emerging technologies, and shifts in the seed sector.”

Eudes outlined AAFC’s efforts along what he calls a “breeding continuum,” integrating emerging disciplines like genomics, gene editing, and artificial intelligence alongside traditional genetics. While this investment in upstream science promises plenty of innovation, it also signals a shift in AAFC’s role in delivering field-ready cultivars.

“We’re committed to plant breeding,” Eudes reassured the audience. “But we recognize we’re not the only science provider. Collaboration with other players is essential to ensure innovations reach the market efficiently.”

Mayer highlighted systemic vulnerabilities that necessitate AAFC’s evolution.

“AAFC plays a critical role, from providing land and infrastructure for variety trials to developing innovations,” she said. “With the resources we have, we want to have the greatest impact for the sector. This means working to be more of an enabler of all players in the market and less of a competitor.”

Mayer also pointed to the realities of government programs like AgriScience. “This reliance on a federal government program and a five-year funding cycle is far from ideal,” she said, given the time required to develop a variety.

The Cost of Inaction

Graf, who during his time with AAFC bred some of Canada’s best-known winter wheat varieties, painted a stark picture of what could happen if Canada fails to establish a robust system to fill the gap left by AAFC’s shifting role.

“Canada has been a bright spot in wheat yield increases globally,” he said, “but if we reduce our capacity for delivering field-ready cultivars and don’t have a solid plan in place to fill that void, the consequences could be dire.”

Graf emphasized the long timelines in plant breeding, often 10 to 12 years from initial cross to market-ready variety. “What’s coming out in the next five years is already in the pipeline,” he said. “By the time we notice a problem, it will be too late, and clawing our way back will be a monumental task.”

Pozniak, who has witnessed these shifts firsthand as CDC director, believes the opportunity lies in fostering innovation through collaboration.

“This isn’t a new conversation,” he noted, referencing decades-old documents discussing similar transitions. “The challenge is ensuring we create a system that incentivizes private-sector investment while maintaining public-sector excellence.”

For Souter, starting her own plant breeding company wasn’t just a career choice — it was a mission borne out of necessity. In 2019, she launched J4 Agri-Science, a Saskatchewan-based startup tackling one of Canada’s most critical agricultural challenges: diversifying the nation’s plant breeding ecosystem in the face of shifting government priorities.

“I grew up on a farm in northeastern Saskatchewan and saw firsthand the entrepreneurial spirit of our grain sector,” she said. “But as I went through grad school, I realized that many crops in Canada relied on just one breeding program. It’s like building an entire industry on a single leg of a stool — one that could collapse under the weight of future challenges.”

Her decision to strike out on her own wasn’t made lightly. Canada’s agricultural sector is at a pivotal moment, and for breeders like her, the challenges are daunting and the need for new funding models is critical.

Around the globe, countries like the UK and Australia transitioned their public breeding programs decades ago, allowing private breeding enterprises to flourish, she noted. In Canada, however, the shift has been slower.

“Plant breeding takes time — 10, 15, even 20 years — and if we don’t act today, the lack of diverse varieties will become painfully clear down the road.”

For Souter, the solution is clear: foster competition and innovation by supporting a diverse ecosystem of breeding programs. “It’s about hedging our bets — ensuring farmers and seed growers have options, and the industry has resilience.”

Pozniak’s insights offered a compelling argument for program-based funding. “Plant breeding is inherently a long-term endeavour,” he said. “Program-based funding provides stability — supporting our people, infrastructure, and core breeding activities. Without it, the work simply can’t continue.”

The CDC operates with a $30 million annual research and operating budget, balanced across contributions from government, growers and industry. These partnerships are critical. He also noted the importance of public and private sector collaboration, and described an innovative collaborative program with Corteva Agriscience, where the two entities work together to improve the nutritional profile of durum wheat.

“They bring technology; we bring germplasm, expertise and know-how. It’s a win-win that showcases the power of collaboration and program-based funding,” he said.

Contrast this with project-based funding, often tied to short-term priorities. “Projects are important, but they can’t replace stable program funding. When projects end, we’re left with expertise and infrastructure we can’t sustain. Long-term stability is the foundation for innovation.”

Graf believes the solution lies in creating better incentives for private companies to invest in plant breeding.

“We need an ecosystem that promotes a return on investment,” he said. Graf advocated for exploring new funding mechanisms, such as endpoint royalties (EPRs), despite their controversial reputation among farmers.

“We can’t rely on the existing system to fill the void left by AAFC’s transition. We need bold ideas and a willingness to try new approaches,” he said, noting an EPR of just one cent per bushel of wheat would generate around $11 million in funding for breeding programs.

Beyond Competition: The Call for Collaboration

Competition has its place — in sports. But in agriculture, collaboration is non-negotiable, Yada said. “We can’t afford to be competitive within the industry. We need to pool resources, share expertise, and work together.”

Eudes echoed this sentiment, urging stakeholders to embrace co-development. “Defining a sustainable funding model isn’t just a government responsibility — it’s a collective effort. We need a broader conversation that involves every stakeholder,” he said.

Mayer said the current Canadian model that funds and delivers varieties poses a risk. “If we don’t collectively pursue alternative funding models, the system risks breaking in ways we don’t want.”

For universities, the stakes are high. Yada underscored the challenge of covering operational costs in light of diminishing provincial transfers. “If partners don’t step up, we can’t run the university or educate and train the students who are your future employees. He called for a shift in the narrative with industry and government partners to explore sustainable funding models.

Yada’s vision includes a provincial database consolidating research, expertise and infrastructure. “Time is our most valuable nonrenewable resource, and we need to use it wisely. We need mechanisms to ensure breeders see returns on their investments.”

Perhaps most importantly, panelists agreed the industry needs champions to come forward and ensure the wheels are put in motion to drive action in securing the future of plant breeding.

“That’s where we all come in. We need to admit there are issues and start real conversations — with farmers, with seed growers, with everyone involved,” Mayer said.

Mayer said the current Canadian model that funds and delivers varieties poses a risk. “If we don’t collectively pursue alternative funding models, the system risks breaking in ways we don’t want.”

Audience member and seed grower Sarah Weigum, who serves as vice-president of the ABCSG, said the discussion was the first time she’s seriously contemplated what the future will be like with AAFC’s shifting role in plant breeding.

“In the past when I heard that AAFC is stepping away from developing field-ready cultivars and shifting its focus upstream, I’ve felt a bit of fear and panic. It’s like, ‘What are we going to do?’ But today, hearing Francois speak, it was the first time I didn’t feel so panicky,” she said.

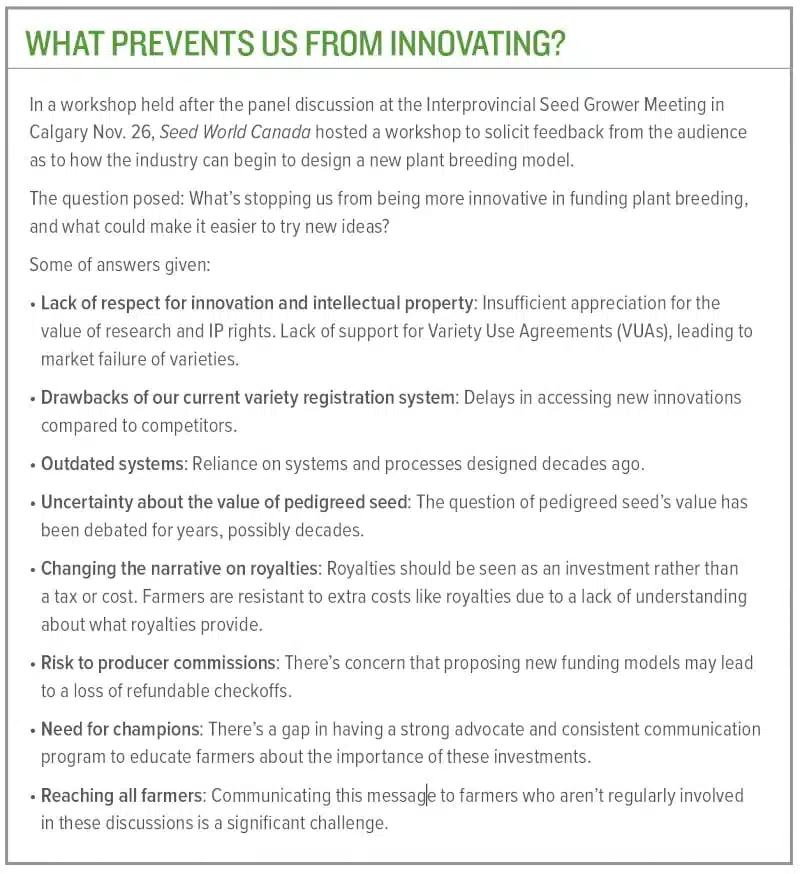

“It was like, ‘Okay, this is how things are going to be, and it’s not the end. We can adapt and create something new.’ I think it’s just about hearing the same message enough times for it to sink in. The real challenge, though, is getting that message to farmers.”