The funding landscape for seed development is more complicated than it used to be. While producer levies are crucial, they’re just one piece of the puzzle.

A significant portion of plant breeding is funded through producer checkoffs, levies collected from farmers when they sell their crops. These funds are directed towards research and development, including plant breeding initiatives, with the goal of improving crop varieties and enhancing agricultural productivity.

While check-off dollars are an important source of funding for plant breeding, University of Saskatchewan economist Stuart Smyth is part of a growing chorus of industry stakeholders sounding the alarm: checkoffs likely cannot be the sole funding source for the development of new seed varieties, and as the world evolves, so does the need for new funding sources to ensure the latest genetics are brought to farmers everywhere.

He helped author the report Economic Impact Assessment of Alberta Grains Research Investments, conducted this year by the Valgen Group and commissioned by Alberta Grains. It shows that from 2012 to 2022, Alberta Grains, using its check-off funding model, invested over $37 million — equivalent to $41.7 million in 2023 dollars when adjusted for inflation, with every dollar invested in variety development generating around $3.80 of value.

“You can see in the report there that Alberts Grains got an exceptionally good rate of return on the investments they’ve made in terms of allocating check-off dollars. That said, one of the highlights that came out of that report is how research today is really a collaborative, effort,” he says.

“You’ve got Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) putting in money, the universities, and then that’s being matched by entities like Alberta Grains, SaskWheat, provincial commodity organizations, the list goes on. We’re seeing a lot of Prairie-wide support for variety development that benefits Alberta farmers.”

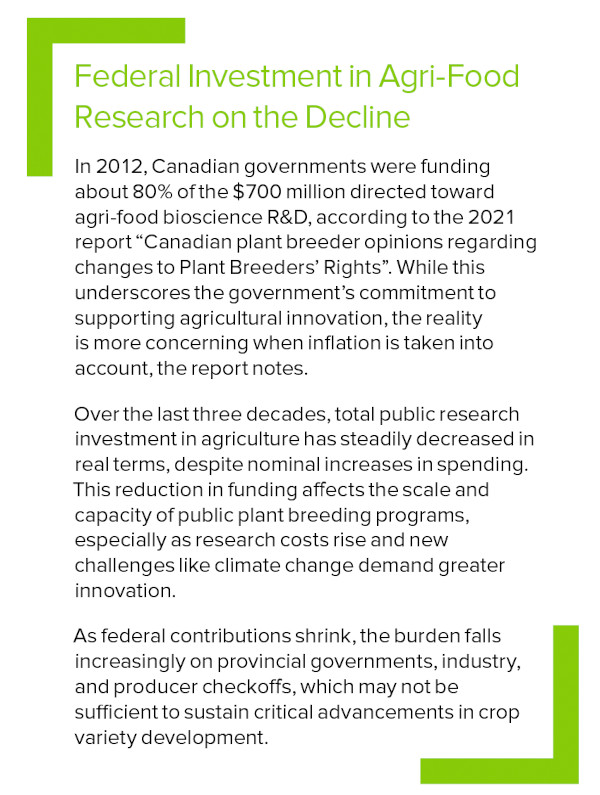

That support is needed as the federal government gradually pulls back funding, something it’s been doing for decades now.

“In an ideal world, the federal government, whether it’s through AAFC or the National Research Council, would put in a little bit higher amount than they’ve been putting in through the five-year research plans AAFC has been using now for just over 20 years,” he says.

“But when you take inflation into account over the last 20 years, ultimately, the federal government is putting less money into variety development than they were 15 or 20 years ago.”

Why?

“At the federal level, there’s a lot of demands on how public dollars are spent. We’ve got health care, immigration, military spending, all these different categories. So, for agriculture to sit at the cabinet table and say, ‘We need an extra $300 million,’ you’ve got to present a really robust case to say this investment will provide real benefits to Canadian agriculture and consumers as a whole,” Smyth says.

“That’s why it’s important for commodity organizations to do these types of studies and say, ‘Look, we’re providing solid value to the Canadian economy with these new varieties of seed that are being developed.’”

Complicated Landscape

Most of the variety development in canola and soybeans is done by the private sector. When it comes to cereals and pulses, it’s primarily done by the public sector, Smyth notes. That means cereals and pulses predominantly rely on public funding sources, but the exact percentage of plant breeding funded by checkoffs varies by crop and region. For example:

- Wheat: Western Canadian farmers contribute to the Western Grains Research Foundation (WGRF) through checkoffs, funding wheat and barley breeding programs. WGRF has provided millions in funding to public breeding programs.

- Pulse crops: Organizations like Pulse Canada also use checkoff funds to support research, including breeding programs for peas, lentils and other pulses.

- Canola: Checkoffs contribute to the Canola Council of Canada, which funds research and development in breeding for traits like yield improvement, disease resistance, and stress tolerance.

These check-offs are often matched by government grants, increasing the total funding available for plant breeding. The exact proportion funded by producer checkoffs can range from a modest contribution to a significant share of the breeding budget, depending on the crop and the specific breeding program.

Not all of the funds go to plant breeding, though. According to the Valgen study, of the $37 million invested by Alberta Grains from 2012-2022, the money was split between five key research areas: variety development, pest management, crop establishment, core agreements, and other essential projects.

This fueled significant innovation in Alberta’s grain industry, addressing both immediate and long-term challenges, with impacts that extended well beyond the province, according to Smyth.

Alberta Grains allocated $19.2 million, or 52% of the total investments, to the development and commercialization of new wheat and barley varieties. The remaining funds supported pre- and post-breeding research.

“If you go back to the early 1970s, public funding really was enough, because rotations in a lot of places were wheat and summer fallow, so if you had good wheat varieties, then you weren’t looking for a lot of other things from a strictly grain-producing perspective,” Smyth notes.

A couple of things have really changed, and are straining the system, he notes.

“We’ve got increased cereal production in terms of oat and barley varieties. We’ve added new pulse varieties over the last 50 years, like pea and lentil. The dollars that have been set aside for variety development have increased demands across a multitude of crop types.”

Making Plant Breeding Sustainable

As sustainability takes centre stage in farming circles, the focus shouldn’t just be on how plant breeding can support sustainability, but rather on how we can sustain breeding and variety development in Canada.

That’s according to Lauren Comin, policy director for Seeds Canada. She notes that traditionally, federal programs like the AgriScience clusters have allowed industry groups to match funding with federal dollars to support public variety development.

However, under the current Sustainable Canadian Agricultural Partnership (SCAP), which began in 2023 and runs through 2028, the focus has shifted to addressing federal policy priorities like reducing greenhouse gas emissions and climate change mitigation, Comin points out.

This shift has led to concerns that variety development, particularly near-commercialization activities, is no longer viewed as impactful for SCAP’s goals.

The federal government’s evolving stance has created a challenge, as producers have relied heavily on public variety development, she says. AAFC’s historical attempts to step back from commercialization stages, including a 2012 proposal and the controversial value creation discussions aimed at implementing a farm-saved seed royalty, have faced strong resistance. Despite efforts to transition AAFC’s role, consultations in 2019 failed to create a nationwide royalty scheme, leaving unresolved issues around the funding and future of public breeding programs.

“So, a bit of a mess has been created over the past decade. If government doesn’t develop alternative funding programs to replace variety development investment through clusters, and the market signals to attract private investment and capacity building have been jammed, we need to agree on a path forward,” Comin says.

“The proportion of producer levies that are directed towards public variety development can be increased, but there are limits here, too. Commission pockets are not bottomless, especially those with smaller production shares, and there are countless other priorities begging for their attention. There is more need for research than there are dollars to go around.”

In the meantime, farmers still need the field performance of new varieties to be adequately assessed. This doesn’t just happen in a lab — it requires real-world trials, notes Jeremy Boychyn, director of research for Alberta Grains. This is where collaboration becomes critical. Alberta Grains recently joined Western Crop Innovations as a member, making a $375,000 contribution to assist it in its breeding work.

“Without strong institutions conducting trials, we can’t fully evaluate how a variety will perform on farms. It’s a collective effort, where breeding institutions pass genetics back and forth, asking questions like, ‘Can you test this in this area?’ or ‘How does it perform under different conditions?’ To do that effectively, those institutions need adequate funding, so they can carry out these trials properly,” Boychyn says.

“The success of new varieties really hinges on how they perform across various regions, and we need robust systems in place to test that. Alberta Grains, for instance, or any breeding institution, doesn’t operate in a vacuum. They work within a larger ecosystem.”

That’s why long-term core breeding agreements are so important now, he adds. They ensure that each institution is contributing value where it’s needed most for Western Canadian producers.

“It’s about making sure that every dollar spent contributes to a bigger picture — identifying gaps, addressing them, and driving results that benefit farmers across the region.”