The seed community has lost a legend who’s being remembered as a seed grower and farmer who knew how to make long-lasting change — sometimes pushing the envelope to do so.

Tom Jackson passed away Aug. 10 at the age of 65. The seed grower (he grew his first pedigreed seed crop at just 17), farmer and joint operator of Jackson Homesteaders Farms in Killam, Alta., was known as an iconoclast who juggled a packed agenda — running for office, staying deeply involved with crop commissions and policy groups and going so far as to serve on both provincial and federal riding associations.

“Tom was always someone who showed up regularly to our meetings and events. He was a familiar face, someone we could count on seeing at all our functions,” says Chelsea Tomlinson, who operates True Seeds in Redwater, Alta., and sits on the board of the Alberta-British Columbia Seed Growers (ABCSG).

“He had a knack for getting more people involved in a conversation, even those who might have been sitting quietly in the back. Sometimes he would play the role of the antagonist, but I think his real goal was to encourage engagement and get more people talking.”

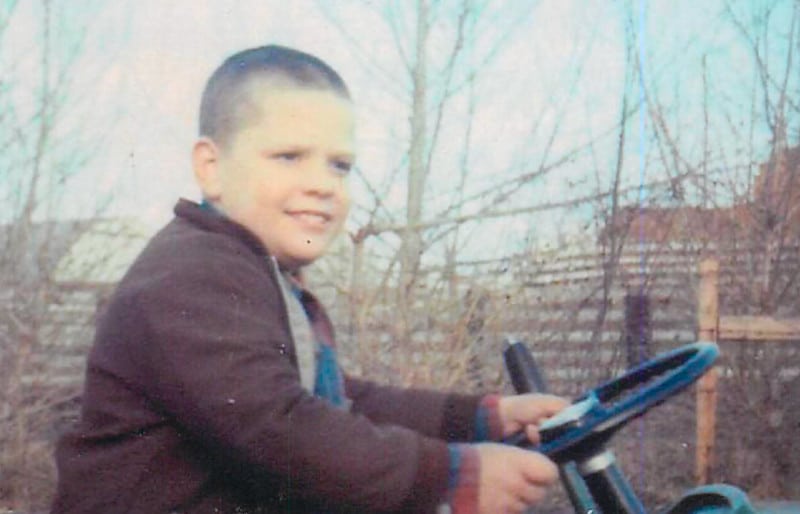

Born in 1958 in Sherwood Park, Alta., he learned the ropes from his dad and uncle, developing a deep commitment to the land, the animals, and most of all, the machinery that kept everything running smoothly on the family grain farm.

In the mid-1970s, Jackson joined the Teen Time of Edmonton Christian youth group (his faith was extremely important to him throughout his life), where a chance encounter at a ranch near Dapp, Alta., changed his life forever. While helping deworm the horses, he met Lucy Wall, who would become the love of his life.

As the 1980s rolled in, so did a new chapter for him. With the arrival of their children Naomi, Daniel, and Joshua between 1982 and 1984, the farm in Sherwood Park took on new meaning, and Jackson found himself transitioning back to full-time work on the land — this time with a family to share in the joys and challenges. But the 1990s brought major changes to farm life for Jackson. As the fields around Sherwood Park gave way to housing developments, his family also grew, with Ruth and Zeke arriving in 1993 and 1995.

That same year, a serious accident forced Jackson’s dad into retirement, prompting his youngest brother Colin to take over managing the family farm in Sherwood Park.

Meanwhile, Jackson turned his focus to advocacy, diving deep into crop commissions and policy groups, and fighting tirelessly for marketing freedom during the contentious Canadian Wheat Board debate. The latter issue would become a huge focus for Jackson.

He went on a much-publicized month-long hunger strike in 1996 to protest the Wheat Board monopoly. His goal? Getting an export license to allow him to ship his grain to the United States. He wasn’t successful, but he ended up devising other ways of making his point that the Wheat Board monopoly was stifling business opportunities for farmers.

“Tom had grown some high-quality hard red winter wheat grain, and he found a market for it south of the border,” says Jim Galloway, a longtime friend of Jackson’s and owner of Galloway Seeds in Fort Saskatchewan, Alta.

“He said he could get about $2 more per bushel selling it there than he could through the Wheat Board, but of course you weren’t allowed to do that. That’s when he learned that you could bypass the Wheat Board by sending pedigreed seed to the U.S.”

Of course, there were requirements — the seed had to be cleaned, inspected, graded, properly documented and bagged.

“Tom came to me and said he wanted to line his trailer with vapour barrier, load the seed — which I would clean and grade for him — and then use our bag closer to stitch the plastic ends of the vapour barrier together, creating one gigantic ‘bag’ in the back of his truck. That way, he could meet the Wheat Board’s requirements.”

That’s exactly what Jackson did. He drove down to the U.S. with his bagged, cleaned wheat seed, bypassed the Wheat Board, and sold it there, Galloway recalls.

“After his trip, I asked him how it went. Tom’s reply was, ‘Well, I’m not in trouble yet.’ That was just the kind of person Tom was — he always tried to prove a point, to help other farmers, and find ways to work within the regulations, even if it was sometimes a bit on the grey side.”

Ken Lopetinsky, considered one of the fathers of Western Canada’s modern-day field pea industry, says Jackson will be a force that will be missed in an industry always grappling with change and how best to meet the future.

Lopetinsky was heavily involved with the Alberta Pulse Growers Association, which he joined in 1983 and which in 1989 became the Alberta Pulse Growers Commission (APG). He remembers Jackson as someone who was in the right place at the right time when pulse growers were grappling with how best to fund seed development after the provincial government began to tighten the purse strings.

“Tom was instrumental in the formation of APG. He climbed right on board and what needed to get done, he helped get done,” Lopetinsky says.

In 2001, Jackson made a bold move, launching a new seed farm just west of Killam. Relocating from the city didn’t slow him down — he continued to push boundaries, experimenting with exotic crops like einkorn wheat and Jerusalem artichoke.

Jackson bought more land and put some of it in son Daniel’s name, thinking that Daniel would eventually take over the farm. In 2020, after living in California, Daniel did come back, and Jackson really began the process of transitioning the farm to the next generation.

“Tom was determined to move as much land as he could into his eldest son’s name,” Lucy says.

“Tom probably felt like he didn’t get that growing up, since his parents handled things much differently in terms of passing the farm on, and he was the eldest son.”

As late as this past spring, despite being ill, Jackson was still making deals, and continuing to make his mark on how things were done at the farm.

“I think my dad felt for a long time that he was preparing something that would become a legacy for someone else to pick up,” Daniel recalls. “He was never really ready to let go, you know? He wasn’t ready to stop being the guy in the field, but he was always open to talking about his plans and what he was thinking.”